The Cure for Fast Fashion

.avif)

When buying new clothes, fast fashion is ubiquitous. It's cheap, but the low cost to customers comes at a high, dangerous cost to garment workers, communities, and the environment. So, how do we break free from the fast fashion cycle?

On this first episode of Second Nature, we're commiserating with listeners over the allure of fast fashion and getting real tips to break free from it. Plus, we're doing the math on the impact of buying less fast fashion and talking to Kestrel Jenkins (journalist and host of Conscious Chatter) about the human cost of fast fashion.

On this episode, you'll hear:

- Practical guidance from real-life, former fast fashion shopaholics.

- An interview with journalist and Conscious Chatter host Kestrel Jenkins about the human cost of fast fashion and how to recenter the supply chain in our buying habits.

- What happens when get this right? Commons CEO and founder Sanchali Seth Pal does the math on how ditching fast fashion can make a real carbon impact.

Here are some listeners you'll hear from in this episode:

.avif)

Citations and further reading

- 45 Fast Fashion Brands to Avoid

- London Textile Forum

- A mountain of used clothes appeared in Chile's desert. Then it went up in flames.

- Income and Poverty Status of Families and Persons: 1984 (Advance Data)

- Spending on apparel over the decades : The Economics Daily

- Average Household Budget: How Much Does the Typical American Spend? - ValuePenguin

- Textiles: Material-Specific Data | US EPA

- It's Time to Break up with Fast Fashion, Vox

- America can't resist fast fashion. Shein, with all its issues, is tailored for it

- New figure put on fashion's carbon footprint | Materials & Production News

- How the fashion industry can reduce its carbon footprint | McKinsey

- Fossil fashion: the hidden reliance of fast fashion on fossil fuels • Changing Markets

- Fashionopolis by Dana Thomas

- New York Fashion Act

- The Garment Worker Center in Los Angeles

- The Garment Worker Protection Act FAQ

Episode credits

- Listener contributions: Alyssa Barber, Drew Crabtree, Freya Dumasia, Hattie Webb, Kellie Rana, Lawrence Hott, Madeline Streilein, Miriam Jornet, Romina Román, Rozalia Agioutanti, Tavia Anon, Willa Stoutenbeek

- Featuring: Kestrel Jenkins and Sanchali Sate Pal

- Editing and engineer: Evan Goodchild

- Fact checking: Sophie Janaskie

- Hosting and production: Katelan Cunningham

{{cta-join2}}

Full Transcript

Katelan: Hello again. Welcome to "Second Nature," a podcast from Commons where we talk to people about how they're living sustainably in an unsustainable world.

The Atacama Desert in northern Chile spans over 40,000 square miles, and it's considered the world's driest desert. If you would have flown over the Atacama in early 2022, you would have seen, among its natural mountains, a mountain of clothes.

It was so big, it was visible from space.

Estimates predict it could have weighed between 11,000 and 59,000 pounds, one to two times the weight of the Brooklyn Bridge.

All those new and used clothes had come in by the container load from all over the world, Europe, the U.S., Korea, Japan. But on June 12, 2022, that huge pile of clothes burned.

As you may imagine, with over 60% of our clothes being made from polyester, the air, it smelled like burning plastic. Grist reported that students on the scene said it was like a war. They said the municipality was essentially fighting an oil fire.

Of the 100 billion garments produced each year, 92 million tons end up in landfills and places like the Atacama Desert. That's a trash truck full of clothes every second getting thrown away. Since you started listening to this episode, that's like 90 trash trucks. So when do we start treating our clothes as disposable? And despite the mountains of clothes piling up around the world, why does fast fashion still have us in a chokehold?

I'm your host, Katelan Cunningham, and I promise this episode of "Second Nature" is not going to be a total downer. Today, we're commiserating with listeners over the addictive allure of fast fashion and giving you all the tools you need to finally sever your ties with your fast fashion Achilles heel, be it Sheehan, Uniqlo, ASOS, Cider, you name it. Today, we're gonna realize the collective carbon potential of fast fashion-free closets. And we're talking to Kestrel Jenkins, the host of the Conscious Chatter podcast. She's going to illuminate the human cost of fast fashion and answer the question, can sustainable fast fashion brands even exist?

Here we go.

(upbeat music)

Katelan: A lot of us know that fast fashion is bad, yet it's everywhere. Most of the big fashion chains and online brands, they're selling fast fashion. We got a lot of listener questions about fashion, which can be pretty well summed up by this one from Hattie Webb in London. Why do people still buy fast fashion when they know it's bad for people in planet? Well, one of the key reasons is because it's cheap.

Accounting for inflation, we're spending about half as much money on clothes than we did over 30 years ago. But we're buying more clothes, a lot more clothes. Some estimates show that we're buying five times more clothes than we were in the 80s. So as clothes have gotten cheaper over time, we've bought more of them. And unfortunately, thrown more of them away. From 1960 to 2019, textile waste increased over eight times at the factory and consumer level.

Clothes got cheaper to buy because they got cheaper to make. And they got cheaper to make at the high cost of exploitation. By underpaying garment workers and paying less for fossil fuel-based fabrics like polyester, brands are exploiting humans, animals, and environmental resources to keep up with the fast pace of fast fashion. And then there are the ultra fast fashion brands like Sheehan. Sheehan releases an estimated 10,000 new styles every day. With all the fossil fuels required for energy, materials, and transit, the fashion industry accounts for an estimated 2 to 4% of global carbon emissions.

Even knowing all that, there are still lots of cute things. And they're on sale all the time.

If you find yourself impulse buying fast fashion or piling up your cart every time there's a sale, you are definitely not alone.

I was definitely a shopaholic.

Willa: A true fashion victim. I used to buy a lot of clothes.

Rozalia: Yeah, like that thirst of continuously having new things to play around with. I get so excited by colors and textures and putting things together and creating new outfits.

Kellie: I was that person that received emails from fast fashion brands, notifying me of their huge sales and I would go absolutely nuts over it. The worst part is that there are some clothes that I literally have never worn.

Rozalia: So just kind of having to rewire my brain to be very creative with what I already have. And you know, I realize that I already have so much. I can play around with it so much. I just need to open my mind more.

Willa: It's such a growing problem and it's growing at such a fast pace. And I don't want to take part in that system.

Madeline: My initial motivation to buy less and shop more intentionally was absolutely frugality. When I was 13, my parents from then on out decided to give me a lump sum every year that would be my responsibility to budget throughout the year. (upbeat music) This worked out to $87 a month. Back then, Levi's were $50.

First thing I did was get a job. I learned pretty quick that my money wasn't gonna get me very far. And I needed to be very thoughtful about what I spent my money on. I was a teenage girl, so I absolutely was interested in fast fashion at the time. Forever 21 was really popular. But over time, I started to watch my clothes fall apart. And I started to really shift my understanding of what wealth was. It wasn't to me anymore the ability to acquire as many things as you want whenever you want them. But for all of the things that you own to be really high quality and to last a long time, yeah. (upbeat music) So there are the cheap fast fashion brands, right? You have your Shein, your TeamU, Amazon, H&M. These can be easier to identify because the prices are so low. But there are other fast fashion brands, like Urban Outfitters, Uniqlo, Anthropologie. These can be a bit harder to spot because the prices start going up. So besides price, how can you identify a fast fashion brand? Here are some things that we look for at Commons.

Fast fashion brands are typically selling hundreds or even thousands of styles with new ones arriving every week. Fast fashion brands typically use a high percentage of fossil fuel-based fabrics like polyester because they're cheaper. And fast fashion brands are not very transparent about their supply chain, especially the pay and treatment of their garment workers. So if you go to their sustainability page, if they even have a sustainability page, and you leave with more questions and answers, that's a big red flag. A transparent supply chain doesn't fix a fast fashion brand's problems, but it does give them less places to hide. At their worst, opaque supply chains can obscure deadly, dangerous shortcuts. That was the case in the Rana Plaza collapse. If you don't remember it, it was sort of a moment of reckoning for the fast fashion industry. The Rana Plaza collapse happened over 10 years ago. Thousands of garment workers in Bangladesh went to work in the Rana Plaza, which wasn't built to code after many warnings and complaints that the building wasn't safe, it tragically collapsed, killing 1,000 people and injuring 2,000 more.

Interview with Kestrel Jenkins

Katelan: It's so important to understand the human costs of the fast fashion supply chain. So I called up Kestrel Jenkins. She's an internationally trained journalist and the creator of the OG Sustainable Fashion Podcast, Conscious Chatter.

Katelan: Hi, Kestrel. Thank you for joining us. Hello, thank you so much for having me. So I wanted to talk a little bit about the Rana Plaza collapse. We were just past the anniversary of it. It happened in 2013 and it felt like a real kind of like moment of reckoning for the fashion industry. And it kind of brought with it this momentum it felt like. But as someone who's outside of fashion, I wonder what your perspective is on, have there been any really big kind of like regulations or laws that have passed as a result of that or in the interim time?

Kestrel: Absolutely, I mean, the Rana Plaza disaster was like literally a horrific disaster. And the thing that's so overwhelming about it is that there were multiple requests and complaints from garment workers working in the factory saying that there were cracks and there were things that were concerning about the building and the structure and they were ignored. And so it's a situation that was avoidable. But since then we have seen changes, which we've definitely not seen enough. But when fashion as an industry is one of the most under regulated spaces, especially in the US and internationally, it's exciting right now. We're in a time where we're finally seeing changes. We have like the international accord that was originally the Bangladesh Accord where brands are signing on to a legally binding document in which they are trying to help then advocate for worker safety. We have the Garment Worker Protection Act, which went into place in 2022 in California specifically, which was largely written and constructed by folks from the Garment Worker Center in Los Angeles. So it was very much a worker led movement. And that was really powerful because it removed the peace rate. So garment workers previously were being paid by the peace not by the hour. And so they were making oftentimes like $6 an hour when our minimum wage is like $15 an hour.

And so that is really massive. And also with that piece of legislation, brands are held accountable for wage theft, which is something that we haven't seen specifically. A lot of times because of the way the fashion industry operates, brands don't own their manufacturing facilities. And so when something happens, they say it was in our third party manufacturing, like we didn't know. We were detached from that, but that's no longer valid. Brands are held accountable to payback wages when they've been stolen or when there's back pay that's needed. So that's exciting. We now have different larger pieces of legislation that have not passed yet, but they're in the works. So for example, the Fabric Act is a federal version of the Garment Worker Protection Act and would take that across the United States, not just in California, because there's many more garment workers across the US.

And we also have the New York Fashion Act, which is working on layers that include supply chain transparency that would affect worker rights ideally, but also environmental rights.

Katelan: Yeah. Wow, that is a lot of things happening. Okay, so I wanted to dive a little bit into kind of like what it takes to make, let's say a t-shirt, right? I was looking on Shein’s website before we hopped on here and there are just probably hundreds of t-shirts that you can buy for $5. So I kind of wanted to know, like, is there a world where a new shirt should ever cost ethically $5 with all sort of the materials and the time and the energy of people and machines and all the things that go into the production of it?

Kestrel: Yeah, I think that's a very good question. I think that we have been trained to think that it's possible to buy a $5 t-shirt and that it's possible to manufacture something like that, which obviously it is being done. But when you think about what's happening behind the scenes, it's like basically impossible to make a garment with all the pieces that go into it. And just, if you literally just think about the labor,

if anyone has tried to sew ever or has even tried to mend something, you know that making something with your hands, which a lot of times people forget this, but in the garment industry, everything is still made by hand. There may be our sewing machines involved, but that is a human operated machine. And so it takes human power in order to create garments. And just for the manufacturing of it from a labor stance, like it's impossible for that sort of a cost. And like you mentioned, when you're thinking about materials and you're thinking about thread and you're thinking about transportation, you know, the fashion industry is very interesting in that it touches almost every other industry. And so it's one of those spaces that's really challenging to calculate what its carbon impact or its impact in general really is because it's touching transportation, it's touching agriculture, because, you know, a lot of our fabrics are grown from crops. It's touching the plastics industry. It's touching fossil fuels because the majority of our garments today are made from synthetic materials, like for 60%. So it touches all of these different spaces. And we have gotten to this place where we totally undervalue what goes on behind the scenes in order to create something. And I think we're seeing that in a lot of the ways that we think about products today, because everything has become so fast. And we have these expectations that are totally unrealistic because, you know, companies like Amazon have allowed this to happen and, you know, you order something and literally it's on your doorstep sometimes the same day.

Katelan: Yes, it's mind boggling.

Kestrel: It's like we have these expectations detached from the reality of what goes on behind the scenes in order to create something.

Marketing has trained us to be detached from it, which is a sad reality, but it's like we have to really slow down and think and ask questions in order to kind of connect the dots about the fact that, okay, this is made from cotton. What does that mean? That means cotton was grown in the fiber, and then that fiber had to be harvested. And then that had to be spun and woven into a fabric or a garment. And then it had to add on different components like buttons or tags or zippers or whatever that is. And then it had to be packaged, it had to be transported. There's like so many steps in the supply chain of a garment.

We've been trained to go to the store, buy something and take it home and think like, oh, well, I bought it, I like it, it fits the end. So the more we can kind of tune into that, I think the more questions that unravel and the more we realize how would it be possible for a t-shirt to cost $5?

Katelan: Yeah, every once in a while or probably more often than I realize a fast fashion brand will have a line of like eco products. H&M has a whole sustainability page about all the recycled materials that they're using, which is good from the sense of a supply chain. If you think of it like, okay, well, H&M can invest a lot of money into the supply chain that small brands probably can't. And so maybe they're gonna get us in the right direction faster, right? But on the other hand, it's still a fast fashion brand. And so I'm just kind of wondering like, is there a way for a fast fashion brand to be sustainable? Is that a thing that we can ever expect to happen or does it kind of go against the very nature of a fast fashion business?

Kestrel: Yeah, I think that's a great question. I mean, I think that a fast fashion brand, like you mentioned, can have an impact in the sense that they are potentially, you know, pushing their dollars toward more preferred fibers or like lower impact materials, which can be powerful on a global scale to an extent. But a lot of times that's going to recycle polyester, which can sometimes lean in its lead into actually the production of more plastics in order to be able to recycle it for the garment industry. So there's that concern. But I think just at the baseline, the fast fashion business model goes entirely against sustainability because it is built on overproduction, producing far more than what the demand is and what is needed. And then through that, pushing people to over-consume. And so those two components, which I think are some of the key like root issues that we need to address to change fashion are basically what fast fashion is all about. And so I don't think in like the fundamentals of a fast fashion brand can be sustainable. I advocate for anybody changing towards a different direction, but the business model really needs to transform in order for there to be change.

Katelan: Okay, I wanted to ask a couple audience questions that we got. We asked folks what their burning climate question is, and we had several fashion questions come up. So we got one question from Romina Román in Barcelona, and she asked,

"How can I find a balance "between encouraging others to buy less clothes "without affecting workers in the industry "that could go jobless as a result of the ablation "of ultra-fast fashion companies?"

Kestrel: I think this is such a consistent question in the space when talking about worker rights and folks being concerned about that because it's like a natural like logic to think, "Oh, well, if I don't put my money here, "then they're gonna be making less fast fashion garments, "and therefore there'll be less jobs," and that sort of a mindset, which definitely like in general makes sense, but as many advocates and folks working in the space have articulated, it's not necessarily true. And also if we want to change things, we have to change our behaviors as well. And so I think it sometimes can be a crutch. It kind of like allows us to keep buying and not thinking about it because we feel like, "Oh, well, if we stop, we're gonna actually, you know, "hurt the supply chain," and that sort of thing. But I think what's really important instead of like asking that question is like, how are we advocating for worker rights and dignity for garment workers? Garment workers, majority are women of color. Majority are far away from us. And so again, like the systems are trying to help us disconnect from that and not realize that they're also people like us. They're also people who have families and all of these desires and hopes and dreams, and the more we can like humanize the reality of the supply chain, the more that we can help change things. And I think there's another part of it that we don't talk about enough in the space, which is financial sustainability.

From all different layers, if someone is not getting paid enough to meet basic needs for their family and for their life, and that is not sustainability, and we have to constantly be reminding ourselves that that also needs to be a part of the conversation.

Katelan: I'm gonna end with one more question. We have someone named Tavia from the UK who asked, “How do I talk to friends and family about climate change and about living more sustainably without sounding like a nag? I feel like whenever I mentioned my sister's fast fashion habit, she just rolls her eyes at me and goes back to buying from Shein.”

Kestrel: Such a good question. And I think it's tricky when we learn information, we wanna share it, and sometimes the way that we approach it can be taken not necessarily in the most welcoming way. So when I kind of entered this space 16 years ago, I was really angry when I realized the inequities of fashion. I was really pissed because I had felt like for all the time that I was buying clothes before that, I didn't know what was actually going. No one told me what the reality was behind the scenes. And so with that rage, I would almost approach people in that way. I was like, aren't you angry with me? Aren't you mad about this too? And no one wants to be approached with that sentiment. You come at someone pissed off, they're not going to be receptive to information. And so I very quickly learned that that was not the approach. I feel like really what is powerful is allowing people to realize that something that they're already doing is a more sustainable option. Because I'm sure that everyone is already doing something that is better. So like, for example, have you ever shared clothes with people in your family? Have you ever like, you know, handed over garments, that sort of thing? That is a really powerful aspect. Sharing clothes, moving them around, like not going and buying something new. And thinking about different ways, like for example, like do you like to walk sometimes instead of drive? Do you like to go on a bike ride instead of take your car? Like, do you like to compost? Do you like to garden? Like whatever that touch point is, they can help people realize that they actually are already a part of this conversation and a part of this movement. It really kind of opens the door for people to want to continue building upon that.

Katelan: I love that advice. Hopefully that's what we're doing with this show. It's making people realize the things that they're already really excited about. Thank you so much.

Kestrel: Yeah, thank you so much for having me. The more that we talk to each other and like just lay all the questions out there, the more we all learn. (upbeat music)

Katelan: Buying fast fashion has become a default for a lot of people and breaking that cycle may be a little bit tricky at first, but we've heard from listeners that it's worth it. Not only to save money and carbon, but to find some clarity.

Here are some tried and true ways to ditch your fast fashion habit. (upbeat music)

Madeline: I try to ask myself when I'm in a store, will the thing that I'm getting be something that I wear at least 10 times? And also will it last through the washing required to wear it that many times?

Freya: Last year, I committed to a no shop year. I just wanted to go call Turkey. And it was really interesting to take note of the moments in which the need for more clothing comes up. And I realized it was always around social. Social moments, social occasions.

Larry: Well, what I've been doing lately is I'm buying clothes of higher quality and in the end it costs me less. I buy pants, I try to get them sized the right way when I buy them, but I take them to a tailor cause I know I will actually use them and not waste them if they really fit me well. - My number one tip for people struggling with buying less is recognizing that it's not a hobby. Find the other free or low cost activities. To avoid shopping, I love attending community swap events. Everyone brings clothes or home items they no longer want. And you get to pick from other stuff for free. That's how I got some of the most worn pieces in my closet last year.

Drew: By using things like Poshmark, I feel like I can still enjoy fashion. But at the same time, when I'm done with some garment or I grow out of something, I can sell it back and I can sell it into the Poshmark community. And so that money becomes cyclical for one and it becomes a self contained sort of ecosystem. But also I'm not putting items in landfill.

Willa: You know, I do sometimes feel like there's a little bit of, you know, that oomph kind of really fun stuff missing in the sustainable slash ethical world. But I mean, if you also know how to navigate secondhand, vintage, there's a lot that can be done. Use your creativity for real and apply the trends with what you already have. If you need to buy, vintage and secondhand is the best option and way more unique than whatever it is in stores.

Kellie: My biggest advice for anyone trying to buy less or shop more secondhand is to really channel those impulses into something more non-materialistic. Like going out with friends to a really nice restaurant, going for a hike, creative work, reflecting and meditating on what is really important to you and how you present that to the world.

Even five years later, I still struggle sometimes but I remember that buying unnecessary stuff will never fulfill me in the same way that caring for each other and caring for the planet does.

WHAT HAPPENS IF WE GET THIS RIGHT with Sanchali Seth Pal

Katelan: I'm sensing a theme. It seems that breaking ourselves free from the fast fashion hamster wheel requires us to stop chasing that constant newness. So what happens when we all buy less clothes and prioritize secondhand shopping and borrowing from friends and neighbors and buying from sustainable clothing brands? Our dollars really do matter and collective change can shift the fashion industry. Commons founder, Sanchali Sate Pal is going to share what happens if we get this right.

Katelan: Hi Sanchali.

Sanchali: Hey Katelan

Katelan: We just heard from a lot of folks who told us stopping buying fast fashion so much but we still are buying so much as a society. So how big is the fashion industry and have we seen it grow since fast fashion has taken off?

Sanchali: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, fast fashion hasn't been around forever. We actually used to live in a slow fashion world and it wasn't that long ago but fast fashion really began about 50 years ago. In the 1970s and 1980s, retailers in the US started outsourcing production of huge volumes of clothing to the developing world and we started seeing that resulting in the same fashions showing up at different retailers. And that's also resulted in huge growth in the fashion industry. It used to be only about $500 billion a year mostly produced in the US and now it's over $2 trillion a year and it's produced all over the world.

Katelan: Wow, so it's quadrupled over the last, what, like 30 years or so?

Sanchali: Yeah, it's a lot.

Katelan: And in all that time, we obviously have enough clothes that we're piling them up in deserts and in landfills. I don't know, do we have enough clothes? Can we just stop making them for a little while?

Sanchali: That's actually a really good question. If you play that out to be kind of extreme, we actually do have enough clothes currently produced in the world to last us for six generations without producing any new clothes.

Katelan: Wow, so I am doing a personal almost no buy clothing here. I'm doing like six items of clothing, which is already very difficult. So I'm guessing that stopping buying clothes for six generations is maybe a little bit too ambitious. Is there something that we can, I don't know, is there a number we can shoot for that's less than that?

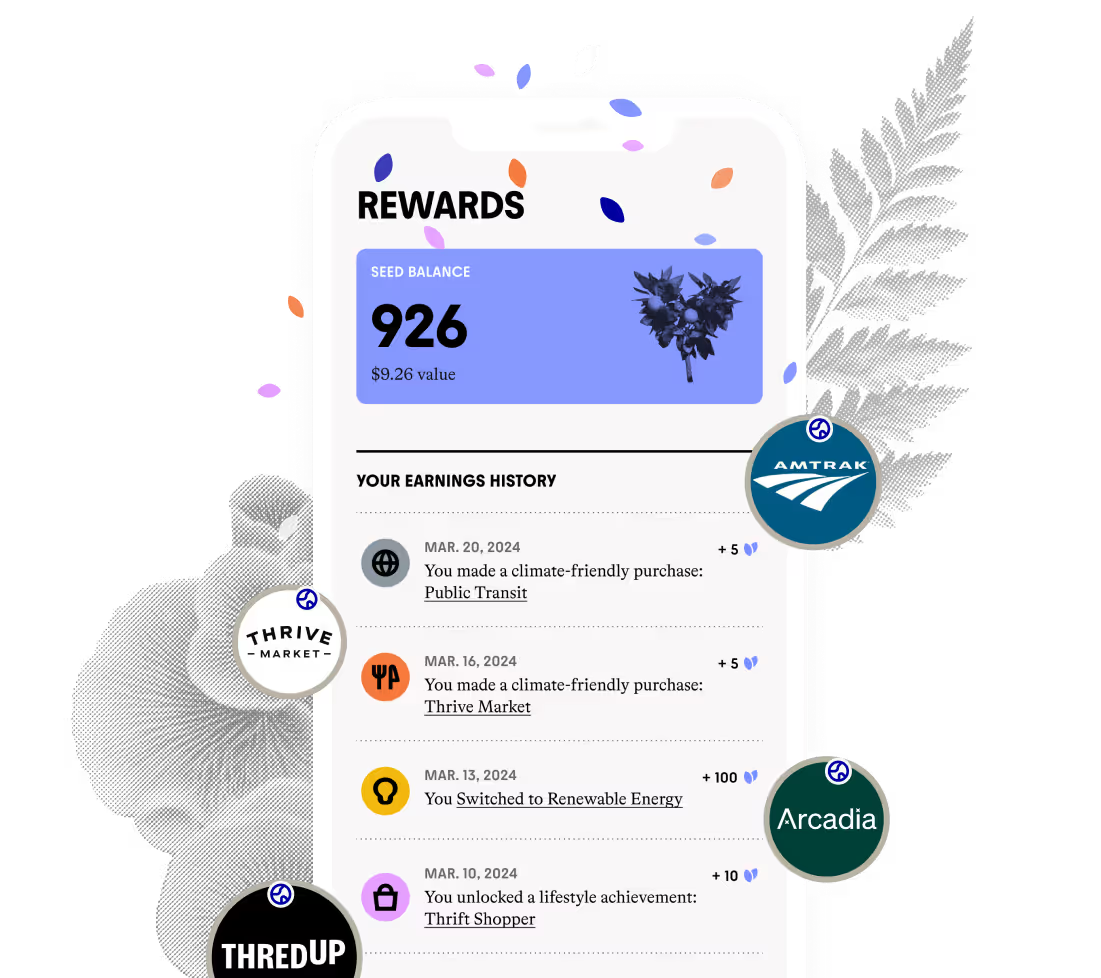

Sanchali: Katelan, you're saying you wanna buy some new clothes? That's crazy. Totally, let's go less extreme. Let's say like maybe we were willing to buy half new clothes and half, we were gonna just use what we already have. Even if we shifted our behavior to just half of that scenario, we'd still avoid about 700 million tons of emissions annually and that would be like taking 166 million cars off the road for a year. That's huge and it's absolutely possible. We have so many ways to buy secondhand now, local thrift stores, online retailers, resale lines within our favorite brands. It's making using what we already have way easier and actually on Commons we're seeing this happen in people's real spending behavior. In 2023, we saw our Commons users buy 92% more from secondhand brands than they did in 2022.

Katelan: So as we start buying more secondhand and hopefully stop buying as many clothes just in general, what kind of impact does that start to have on the supply chain and like, how can we just be more mindful of the supply chain when we're shopping for clothes?

Sanchali: Yeah, I think it's super helpful to think about the supply chain and the carbon supply chain in particular when we're thinking about how to have an impact. So, the reason why rewear lines make a difference is because about three quarters of the emissions of the whole clothing industry come from the materials and manufacturing. If we wanna reduce manufacturing emissions, we can obviously buy less stuff, but we can also buy more sustainable materials. Like we can avoid more synthetic materials and fibers like polyester, synthetic fiber production is actually increasing. And in 2030, it's forecasted to account for two times the greenhouse gas emissions of Australia. So one is purchasing better materials, which is huge. And then we can also buy from brands that have more energy efficient processes, which can also make a pretty big difference in energy use.

Katelan: Yeah, and I feel like if we follow those two rules you just gave us, we're already not shopping at fast fashion companies because those are kind of two of the key things that they do in order to like save money and charge less for their clothes and like pay their workers less as well.

Sanchali: Yes, totally. So materials is a place we can make a big difference. We can also make a big difference in the phase of how we use our clothes. People don't realize that the ways that we wash and dry our clothes are actually the second biggest impact we have in our fashion choices. So things like air drying our clothes can be really effective. It saves us home energy. It also extends our clothing's life. And we can manage them and repair them and wash out stains to make sure that we're not throwing them away too early. - Love that. One of my favorite things to do too is like to dye my clothes whenever they get too stained because then you just have a different color of the same shirt that you love and you can just cover the stain with dye. - Oh my gosh, I love that. That's so creative.

Katelan: Caring better for our clothes is something that we often neglect. What about when we're done with them though? What if we've evolved our style, we're ready to move on. Is there some way that we can responsibly get rid of our clothes?

Sanchali: One is that we can donate them, but the challenge with donation is that actually the majority of clothes that are donated end up in trash in landfill, which it can be really depressing, but it also makes it even more important to be creative and thoughtful about how we get rid of our clothes. So if you're thinking about passing on your clothes, think about if you can share them with friends, do a clothing swap, sell them or give them away to a local thrift store or to people that you know will actually use them. You can also put them up on your Buy Nothing group. You can donate them to people who need them in places that you actually know, or you can recycle them with trustworthy companies. Like for instance, I've been using the take back bag for things that are really hard to imagine someone else might use, like no one's gonna use underwear or like socks with holes in them or like stained towels. So those kinds of things, just recognizing they're probably gonna end up in landfill. So I might as well recycle them.

Katelan: That's really nice. I also like giving to local mutual aid groups because they have a direct use for them and they can just like take your clothes and directly usually give them to other people in your community, which is nice.

Sanchali: Oh, that's really nice. And it's a nice way to like connect with people who live near you.

Katelan: As you've been growing a human inside you, you've been talking to me about how you've been getting clothes from other people in your family to avoid having to buy so many new clothes for yourself.

Sanchali: Yeah, so yes, I'm pregnant. And one of the things that I didn't really realize, I thought a lot about like, I'm gonna have to buy a lot of new clothes for this new human who's showing up, but I didn't really think about how much my own body was gonna change and how much I would need new clothes. And it's really hard to bring myself to buy new stuff that I know I'm only gonna use for a few months. So some of the things I've been doing are,

I've been, of course, asking folks I know if they have maternity clothes they're no longer using that I could use and borrow them maybe and give them back if they're thinking about having another kid later. I also realized that maternity clothes are actually just larger clothes. So I've just been asking people who I know who are a couple sizes bigger than me, if they're willing to lend me some clothes. So that includes my husband and my mom. And they've been so generous about lending me things and they're really happy to help with something really specific, which is really nice. I've also been looking in my local buy nothing group. There's definitely some moms who live on my block who I've now been able to meet through my buy nothing group who have been happily purging their closet of things they no longer need.

Katelan: Nice, I think that's such a good example because we do have these occasions in our life that prompt us to buy something that we're perhaps have no intention of keeping for a very long time. And that's often when we go to fast fashion. And so it's exciting to hear that there are other ways to go about fulfilling these short-term fashion needs that we might have. Thank you so much for giving us the big picture. - Thanks for having me.

Katelan: Who would have thought all this time the cure for fast fashion has just been to slow down, to buy less, less often. And when we do buy, let's buy with more intention to foster a safer, more sustainable, equitable fashion supply chain.

Now, does that mean you should go and toss all your fast fashion clothes right into the trash? Please don't. Wear them for as long as possible. Restyle them, repair them, dye them, swap them. Let's continue developing our personal style by reinventing what already exists. Let's host clothing swaps, shop secondhand, and support sustainable brands.

One super easy action you can take right now is to unsubscribe from all those fast fashion emails and unfollow those fast fashion brands on social media to remove the temptation. Then get a buddy.

Send this episode to a friend so you can motivate each other to skip fast fashion together. If you want to get a list of dozens of the top fast fashion brands, go to the show notes and you will find it there. I want to thank all the listeners who contributed to this episode. You were so generous and open in sharing your own fast fashion experiences and advice. On this episode, you heard from [credits list]

We'd love to hear from you too. If you'd like to submit to the show, go to thecommons.earth.com slash podcast. Second Nature is a podcast by Commons. The Commons app is the perfect way to start tracking your sustainable spending progress. In the app, you can browse a directory full of sustainable brands, including fashion brands and secondhand stores. Plus you will earn rewards for every climate friendly purchase. Go to thecommons.earth slash secondnature to join the app. And you can join our community on Instagram. Follow the show at secondnatureearth. Our editor and engineer on this episode and every episode is Evan Goodchild with fact checking by Commons own carbon strategy manager, Sophie Janeski. It was written and produced by me, Caitlin Cunningham. For citations and further reading, don't forget to check the show notes.

And next week, we're gonna find solace in city life as we learn to grow our own food at home in our urban gardens.

But before we go, let's hear from listener Rozalia in North Carolina. She shared what happened when she slowed down her clothes buying habits. (soft music)

Rozalia: I feel more calm, much more calm.

So much less clutter.

I have more clarity and feels more authentic.