Does it Really Matter If I Eat Less Meat?

Plant-focused eating is one of the most impactful climate actions we can take, but changing our diets can feel overwhelming. Food is not only essential, it's habitual, emotional, and rooted in tradition and culture.

On this first episode of Second Nature, we're hearing from listeners about how they've started adding more plants to their plates, finding inspiration in delicious recipes, and getting inspiration from the power of our collective action.

On this episode, you'll hear:

- Motivation and practical tips from listeners across the plant-forward spectrum: flexitarians, vegetarians, and vegans.

- An interview with food writer Alicia Kennedy about how the food industry needs to reckon with the environmental impact of meat, plus delicious plant-based recipes to try.

- How our collective shift to more plant-based meals can impact the meat industry.

Here are some listeners you'll hear from in this episode:

Citations and further reading

- Meat and Dairy Production - Our World in Data

- How much of global greenhouse gas emissions come from food? - Our World in Data

- Food production is responsible for one-quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions - Our World in Data

- You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local - Our World in Data

- Greenhouse gas emissions per 100 grams of protein - Our World in Data

- Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator | US EPA

- The powerful role of household actions in solving climate change, Project Drawdown

- Alicia Kennedy’s recipes

- No Meat Required: The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating by Alicia Kennedy

Episode credits

- Listener contributions: Amea Wadsworth, Caitlyn Luitjens, Daria Panova, Drew Crabtree, Jacqueline Elliott , Joëlle Provost , Kimberly Foley, Lawrence Hott, Melissa Athina, Timmin Vooijs, Willa Stoutenbeek

- Featuring: Alicia Kennedy and Sanchali Seth Pal

- Editing and engineer: Evan Goodchild

- Fact checking: Sophie Janaskie

- Hosting and production: Katelan Cunningham

{{cta-join2}}

Full Transcript

Hi, welcome to Second Nature. This is a podcast from Commons where we talk to people about how they're living sustainably in an unsustainable world.

In this first season, we got dozens of submissions from people wanting to tell us all about their sustainable lives. And the most common thing that people wanted to talk about was food. Most of us are lucky enough that we get to ask ourselves multiple times a day, "What do I want to eat?" So it makes sense that in our quest to live sustainably, a lot of us have prioritized food. And there's data to back this up. Project Drawdown is a trusted climate mitigation project. They cite plant-rich diet as one of the highest impact actions for households and individuals.

I'm your host, Katelan Cunningham, and on this episode of "Second Nature," we will hear straight from listeners about why they're adding more plants to their plates and if this collective shift actually makes a dent in the meat industry. Plus, food writer Alicia Kennedy shares a bit about the cultural history of plant-based eating and how she makes a great mushroom pate.

Let's dig in.

Picture this. You're reading through the menu at a local, fast, casual restaurant. What kinds of dishes do you see?

I'd wager that most of them are some variation of a meat with a couple sides, maybe hamburger and fries, steak and potatoes. In many countries, meat takes up a hefty portion of our plates. It's kind of like the default. That's certainly the case here in the U.S. Americans are among some of the top meat eaters in the world. Our per capita ranking shifts each year, but we're usually in the top 10. In 2021, we were number seven. Studies estimate that food accounts for anywhere from one quarter to one third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and over half of those emissions can be attributed to, you guessed it, meat and fish production.

Now, meat emissions come from several sources, but the biggest ones by far are land use and farming. Land use emissions arise when we chop down trees and other plants to make space for grazing and building required for meat production. Those plants and the soil around them, they were capturing a lot of carbon emissions. When we clear that land, those emissions end up back in the atmosphere. A lot of farming emissions are methane from, well, cow burps and the burps of other grazing animals. Agricultural methane can also come from fertilizers, manure, rice production, and farm machinery.

So just how high of emissions are we talking here? To answer that question, let's look at a couple kebabs.

One made with beef, the other falafel. That beef kebab has about 130 times the emissions of the falafel kebab, which is primarily made of chickpeas.

Now, maybe it's been a minute since you've had a kebab, but in Germany, they sell 2 million per day, most of them made with meat.

Imagine if just half those kebabs, 1 million of them, were made with falafel instead of beef. After one year, kebab emissions would be down over 6 million metric tons. That's the emissions of over 1.5 million gas-powered cars driving for one year. I know that's kind of hard to imagine, but to give you a visual of 1.5 million cars, it would be like if there was bumper-to-bumper traffic on a four-lane freeway all the way up the West Coast, from San Diego to Portland, and all those cars just stopped running for an entire year.

So, yeah. When it comes to climate change, meat really does matter.

Of course, there's more to all of this than falafel. There are many more motivations for people to eat less meat besides climate. We heard from flexitarians, vegetarians, and vegans about why they started eating less meat and more plants, and here's what they said.

I began side-eyeing the meat industry after my younger sister traumatized herself watching documentaries.

Timmin Vooijs: I became a vegetarian in 2018, to be really honest, simply because the prices of plant-based alternatives became lower than the same product as meat.

Larry Hott: Well, I started in the 1970s when I became a vegetarian because I was so scared of the chemicals that were in meat.

Kim Foley: I started eating no meat when my daughter was about 10.

Amea Wadsworth: I went vegetarian when I was 10

Kim Foley: and disgusted with a rare steak on her plate.

Amea Wadsworth: I did not like the idea of eating a living, breathing animal.

Daria Panova: Physically, I'm very healthy because I'm vegan. I would say that I feel strong and I feel powerful, and I also feel great being powered by plants.

Drew Crabtree: You know, it was a rare instance when I felt like I was in the middle of this big venn diagram, and I could experience and enjoy and contribute positively to all these things that I cared about through one choice, and I proved to be very additive. Mentally, I don't think diet had any impact on my emotional or cognitive well-being, but morally, I feel good about making mindful dietary choices and doing what I can to support climate change mitigation. I stand by it, I feel like it's the right thing to do. I don't feel it's super difficult to, for instance, cut out meat altogether. I mentally, I feel a lot better because I don't feel like I'm making decisions that don't align with my values anymore. I feel much better about saving not just baby chicks, but all sorts of animals, and I know it is much, much better and less emissions for the Earth, so I feel really good about that.

It seems that the way we think about plant-based eating has really changed over time. If you don't want to take on the new title or identity of vegetarian or vegan, you don't have to. In fact, for many people, sticking to those strict rules can make it really difficult to sustain a plant-forward diet in the long term. It's also crucial to consider that in a world where the foods of many cultures revolve around meat, plant-centered meals are not always easy or accessible. Just remember that you don't have to make one big switch all at once. You could try Meatless Mondays or only eating meat at dinner. We ask folks for their advice to start eating more plant-based meals, and we found out that, surprise, surprise, everybody's different. It's all about making gradual shifts that make sense for your life.

Advice from the community to start your plant-based eating journey

Jacqueline: What plant-based eating looks like for me is, I'd like about 90% I'd say, vegan with periodic vegetarian moments, if you will. When I started originally, I gave myself these "sheets" I'd allow a few times a year. Things that I could never imagine giving up, like sushi or tri-tip or my family makes the best ribs in the world. And it's really funny because the longer I've been without these things, the less I miss it. I don't even crave these things anymore.

Drew Crabtree: My approach to plant-based eating is very flexible. I'm generally very rigid, binary person. I like clarity and I like rules. So for me, there is some clarity and ease in the rigidity of, "I don't eat meat." Full stop.

But at the same time, I live in a city and sometimes you're out and there isn't a good non-meat option or something like that. And so fish sort of started to fill in that space, if I need that extra protein or something like that. But similarly, like when we travel, the whole thing becomes more flexible. You have to adjust.

Joelle: What I mainly do is I shop at farmer's markets and I shop at natural food stores in the bulk section and the produce section. There's sort of this misconception that buying this way is going to really break the bank. But in fact, buying in bulk, because it's higher quantity, it lowers the price for the most part. So when you focus on bulk and you focus on produce, that means it's really, really easy to not eat meat. You're able to find a wide variety of different grains and legumes and nuts and seeds that are all kind of exciting once you get past the hump of it not being sort of this typical American diet. And then the really great silver lining is that it reduces our plastic intake too because the bulk, at least where we are, comes in paper and we just bring our own bags for the produce. For me, it's like really an exciting way to eat less meat.

Amea Wadsworth: So I think if you're wanting to go fully plant-based and you're jumping into a cold turkey rather than slowly transitioning, don't eat substitutes for a little while to let your brain forget about the taste of meat and dairy products. And then when you do finally eat substitutes, they will taste totally good and fine. And it's also an opportunity for you to learn how to cook plant-based meals and center your food choices around things that aren't meat and dairy, which we're really used to doing in a society that relies really heavily on animal agriculture.

I love that advice from Amea Wadsworth, who happens to be our social media manager here at Commons. Rather than jumping straight from chicken to faux chicken, there's a whole world of vegetables and fungi to explore. What if our plant-based meals aren't meant to replicate or live up to meat, but instead stand out as their own delicious texturally unique new culinary journey? With all the emotion and culture and tradition that we have rooted in a food, how can we get excited to explore new flavors, smells, and textures? I think a great first step is to eat some really delicious plants.

Alicia Kennedy is a food and culture writer who splits her time between New York and Puerto Rico. Her work has been featured in Bon Appetit, Eater, Harper's Bazaar, and more. And last year, she released her first book, No Meat Required, The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating.

Interview with Alicia Kennedy

Katelan: Hello, Alicia.

Alicia: Hi, thanks so much for having me.

Katelan: So in the opening of your book, you described this process of preparing a banana blossom to cook it, and I have never eaten a banana blossom or been served a banana blossom. And so are there any sort of like more of your favorite surprising foods that you like to cook with? As a food journalist, I'm sure you've like encountered a lot of fruits and veg that everyday folks aren't eating all the time.

So I'm wondering if there are any surprising plants that you like to cook with?

Alicia: Not necessarily. I think it's interesting because I do spend most of my time here in Puerto Rico in a tropical area. So of course, I'm, you know, I have carambola, I have chayote, I have different varieties of plantains, I have guava of different varieties and different fruits. And so, you know, I don't think that they're that shocking.

I think that in a place where a lot of fruit and vegetables are grown at not a scale level, at a subsistence level, sometimes I'm obviously going to the farmers market every week and getting my vegetables and getting fruits there. But also you'll sometimes just be gifted, you know, some chayote because someone's tree is giving a lot of chayote. Or you'll be gifted mango or you'll be gifted guava because the trees are giving that. And so it's really just a different relationship to fruit and vegetables, a bit more of a closeness, I suppose, to their growing.

There can be kind of this parochial notion of like, oh, if you live on an island or something like that, like, yeah, you're closer to the land. And it's not that kind of relationship because I think you could have that relationship to food in New York City.

There can be kind of this parochial notion of like, oh, if you live on an island or something like that, like, yeah, you're closer to the land. And it's not that kind of relationship because I think you could have that relationship to food in New York City.

If you are aware of where the food is, you know, you can find apples in public spaces. You can find pawpaws in different areas. You'll find different berries growing, different leafy greens. So it's really just about that awareness and where people have been able to cultivate that awareness and not be cut off from it and where people have been, you know, very explicitly cut off from the awareness of what edible items are around them.

Katelan: Got it. So kind of a seek and you shall find mentality.

So there's this idea, I feel like in America that, you know, you have your hunk of meat in the middle of the plate and then you have a couple little small things on the side. And you say in your book that that's sort of a European concept. And so I'm wondering what Americans and Europeans and other meat-centered cultures can learn from other parts of the world where meat is secondary or tertiary to different forms of vegetables.

Alicia: Well, I mean, it makes sense for certain types of climates to be more reliant on grazing animals, of course. But the situation that has evolved in the United States, especially, is toward like the factory farming industrial system of maintaining livestock. And so that's where the real problems are because it's not just about housing them in the land that that takes up, but it's also about feeding them.

And, you know, we use 80 percent of agricultural land to just grow like the corn and the soy for feeding livestock. And because of that system, there's this like false sense of over-identification with meat in the U.S. and like a false sense of how important it is because no one goes to a supermarket in the U.S., I'm pretty sure, wherever you are. And there's not like meat there somewhere, whether it's frozen Tyson chicken nuggets or it's steak or it is whatever it is.

And so there's this notion that it's a well that never runs dry, even though it's based upon the suffering of animals.

It's based also on environmental destruction and it's based upon very poor working conditions for people in meat processing. The thing that can be learned, well, it's from the past and it's also from, you know, different places now where meat retains a sort of celebratory stature where animals are reared and used in ways that are not industrialized and are sort of going along with the seasons in a way that makes sense. Yeah, I'm really glad you brought up seasonal eating. I actually kind of wonder, I feel like when you focus on seasonal eating, it sort of kind of forces you to focus on fruit and vegetables, because like you're saying, right, we don't think about seasonality of hamburgers. And so I wonder in your own practice and your own writing how you've seen those two overlap, a focus on plant based eating and then a sort of rededication to seasonal eating. I mean, I think if you're focused on plants, you have that you don't have to be because you could go to a supermarket to get tomatoes in January or maybe you live somewhere where tomatoes are delicious in January. But to focus on plants, it means also that you want the best plants. So you want them to be the freshest ones.

I don't really have an interest in eating a tomato when it's not really red and delicious and juicy. Like that's depressing to me. I don't have an interest in biting into like a cotton ball strawberry that's completely white in the middle, but really big and it comes in a plastic shell. Like that's just not something that's going to give me joy. I don't think it's interesting to eat a mealy apple from Chile in Puerto Rico when I can, you know, maybe I'll be home in New York in the fall and I'll eat a really good apple. Like so to me, because I have this like really big interest in the aesthetics of food and the pleasure of food and also because I don't eat meat.

For me, it's very, very important that the vegetables, the fruits, they're not secondary to anything.

They are the prime thing that I'm eating. And it's for ethical reasons of wanting to support local economies and not wanting my food to move that far on the planet. But it's also about my enjoyment of that experience. Then I think that when people go plant-based or they move, they start to eat meat a lot more thoughtfully. They do find like, oh, like all these things that maybe I was thinking of spinach or broccoli as these things that are just like something I have to eat. Now I understand them differently as like something I can make into something really delicious and beautiful.

Katelan: I love that. You've featured dozens of plant-based recipes in your newsletter over the past couple of years. I wondered what were some of your favorites and like what were some that you got the best and most exciting feedback on if you could describe them for us.

Alicia: Well, I think people really love a mushroom pate, which is interesting because it's really about bringing out the richness, the earthiness, the deep meatiness, so to speak, of the mushrooms and mixing that with herbs and spices. And people really, really enjoyed that. And it's been a very popular recipe. You know, I do a lot of cake recipes that are very pantry-based. And so they're vegan cakes, but you can make them with basically stuff that you'd usually have around.

So I'm very focused on not demanding that someone have a lot of special things in their pantry in order to make a vegan cake. And I think that that level of accessibility helps people to understand that, like, you know, you can easily make something vegan and delicious and it doesn't have to be a big process and you don't have to go to Whole Foods and spend one hundred dollars. Like, no, you can do a really easy vegan cake with some flour, olive oil, sugar and like maybe some cornstarch you have in the back of the pantry. It's really not a complicated way of eating and doing things. And it can be an affordable way of doing things. I think that people would be surprised by what can be popular if you can take animal products out and let these other ingredients shine. Like, people are really surprising in their in their tastes. Yeah.

Katelan: Yeah. I feel like maybe this is kind of like an overconsumption bit of brain, but where it's like you sort of take on a new lifestyle and you feel like what do I need to buy now? What do I know? What's my list? And so I love the idea that it's like what do you already have that you can sort of tap into and use and then sort of like, yeah, finish going through your meat. Don't let it go to waste. But then when you need to restock, go to the farmer's market, you know, and get some vegetables.

Alicia: Yeah. It's easy for me to think about because I haven't eaten meat in so long. But I think that when, yeah, when people start to pull meat out of their diet or eat it more thoughtfully, that it is a lot of like, what do I replace this with? And I think that that's the wrong way to start from. It's just what can I eat more of that I really enjoy and that's going to make sure I'm filling this nutritional hole that I've created. We got some questions. So this is a submission based show and we got several questions about food. And one of them I think is very prevalent for you. I love how in your book you touch on how food touches all these different things, how it touches climate, how it touches supply chains and all these things. And so one person named Dario who lives in Washington, D.C. asked, why don't we communicate connection between diets and climate as much?

Even the research shows that the link between these two things is not very clear for a lot of folks. So in researching your book, why do you think that is? I mean, I think that's by design. It's really, you know, I mean, if you opened up a food magazine or you opened up a newspaper food section, you're probably not going to get the sense that there's a problem. All the recipes are going to be like, yeah, roast a chicken, make a steak, eat pork. Like there's no sense of the issues. I mean, shrimp, too, has I think shrimp is right after cattle, honestly, in terms of impact. It's pretty high up there. It's pretty high up there because of the destruction of mangroves in Southeast Asia. So it causes a lot of problems. And so you're just never going to guess that sense.

And I think that for me, being a food writer and writing about these things, it's about trying to find people in that gap. People who are interested in food are also the people who need to know what foods impact on the planet is. They need to know that there are issues in agriculture that the government subsidizes the grains that feed livestock. The government subsidizes, you know, industrial meat and dairy. It's very much by design that we have an abundance of cheap meat and dairy in the United States. And we do not have an abundance of cheap fruits and vegetables grown consciously and in regional food systems. And so it would cost a lot of money for people who've been doing very well to restructure the system in order to be aligned with ecological limits. And I think that that's just a very daunting task. I think it's also a very daunting task for people to feel individually any sort of responsibility for big systemic problems. And so it can feel daunting and like, oh, I have to change everything about myself, but I don't see anyone else doing it. And so I think that that's also very daunting and that's very real and that's very understandable. The role of journalists and of writers in this moment is to meet people in that and explain it and demystify it. And help people understand where their individual choices do have some impact or will have some sway over how things are done in the future. To change the impact of agriculture on climate change.

Katelan: I just have one more question. I would be remiss if I didn't ask about your vegan mofongo. If you could tell us a little bit about what traditional mofongo is and how it's made and then how you adapted the recipe.

Alicia: So traditional mofongo is going to have chicharrones in it, which is like fried pork skins. And the version that I do, I instead of the pork mix some white miso with smoked paprika in order to give kind of the depth of flavor, the depth of saltiness from the miso and then the smoke from the smoked paprika. Like there's a product called liquid smoke that I think tastes too artificial to me. But I think that smoked paprika with miso kind of gives you the right vibe.

Obviously it's very different still from like a mofongo made with pork, but it gives you still that kind of depth of flavor that you want. And yeah, mofongo is just you mash up the fried plantains with your seasonings and garlic, obviously. And then, yeah, you serve usually with like a saucy protein or saucy vegetable accompaniment. And so it's a very delicious staple food here in Puerto Rico. But yeah, I do that vegan version with miso and smoked paprika. And I think it's one of those little tricks that you learn not eating meat is you don't want things to always taste just like it, but you think about what is the meat doing here and how can I and what is it providing and how can I recreate that without, you know, being obsessed with getting it one to one because you're never you're never going to do that.

Katelan: Yeah, I love that. I feel like that's kind of a big takeaway of this episode is like we don't need to replicate a big hunk of something in the middle of our plates. Yes. We can think outside of that. We can explore some other options and kind of rethink the role of meat and how we can rely on it a lot less, hopefully.

Alicia: Yes. Awesome. Well, thank you so much. This has been so nice talking to you.

Katelan: Thank you so much for having me.

So if we all start eating less meat, does it actually make a difference?

Sanchali Sate Pal is the founder of Commons and her sustainability journey actually started with food. I asked her what kind of carbon impact we would have if we all started eating less meat.

What Happens if We Get This Right with Sanchali Sate Pal

I began really examining my environmental impact when I started thinking more deeply about what I ate as a senior in college. I saw the documentary Food Inc. It opened my eyes to the systems behind my food. I was appalled as an economics major. I began to wonder how can collective shifts in our diet shape the market? What would happen if I ate less meat or if we all did? This was my first foray into carbon tracking. So I built a spreadsheet tracker to estimate the energy and resource implications of my food choices.

I found that by cutting my meat intake from 12 servings a week to two servings a week, I'd have an impact like taking half a car off the road every year. And if everyone in my dining hall did that, we'd take 50 cars off the road every year.

Since that day 12 years ago, I've kept my meat intake to an average of one serving a week, having an impact now like taking seven cars off the road for a year over that time. I've also saved thousands of dollars by shifting to a more plant-centered diet.

But the real impact comes from the fact that it's not just me making changes. According to the USDA, red meat consumption has declined over the last 50 years, as Americans replace beef with chicken, fish, and other plant-based protein sources. Beef consumption in the U.S. dropped 29 percent between 1970 and 2022.

And beef produces 10 times the greenhouse gas emissions of poultry and 20 to 60 times more emissions than plant-based proteins. So this matters. A lot of people making small changes matters more than just a few people making extreme changes. And you're probably seeing these effects of collective action ripple out across your grocery store shelves and cafe menus.

Plant-based milks and meats grew from a $2 billion industry in 2018 to a $20 billion industry in 2023. Some estimates have it reaching nearly $80 billion by 2030.

According to the Good Food Institute, in 2023, nearly half of U.S. households purchased plant-based milk or meat. Sustainability is about finding actions that we can sustain and that will sustain all of us if we do them together. The more we eat plant-based food at home with our friends and families, the more we can demonstrate that we want good plant-based options to become the default. [Music]

Outro

Whether you're a lifetime vegan or you want to take your first steps with Meatless Mondays, I really hope this episode gave you some inspiration to eat delicious plant-based foods and maybe encourage some friends to join you. We received so many great submissions from people about their own plant-based eating journeys. Thanks for all the great contributions. On this episode, you heard from Kim Foley, the mayor of Wattsworth, Larry Haught, Will Astautamake, Jackie, Drew Crabtree, Joel Provost, Kaitlyn Luciens, Timon Voix, Dari Panova.

Our editor and engineer on this episode was Evan Goodchild. It was written and produced by me, Katelan Cunningham, with fact-checking by Sophie Janaskie.

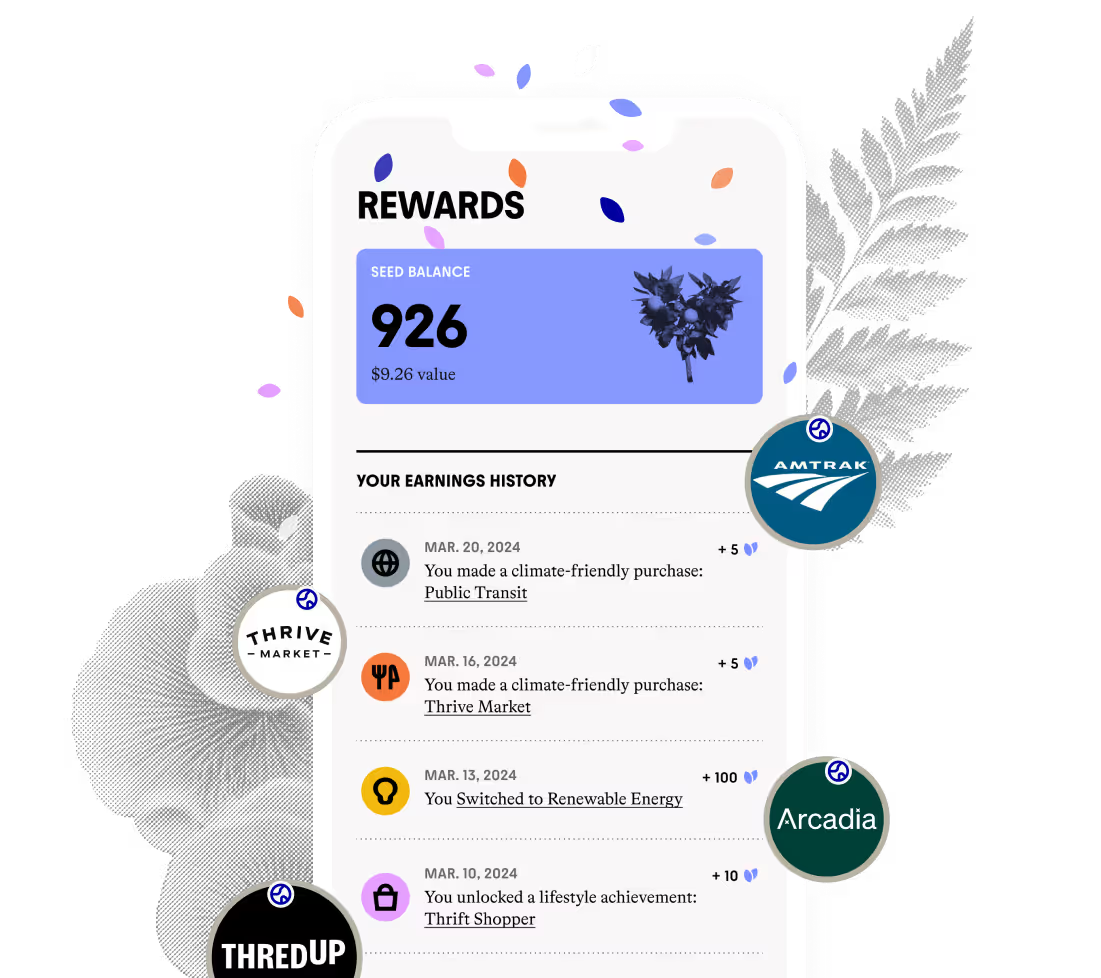

And in case you didn't know, Second Nature is a podcast by Commons, the sustainable spending app that tens of thousands of people use to track their footprint. Earn rewards for climate-friendly purchases like plant-based restaurants, and join collective challenges. Go to thecommons.earth.org to download the app and join this month's collective challenge, Secondhand Shopping.

We're just getting started on this exciting new podcast journey, and we're so happy that you joined us. We'd love to hear what you think of the show. Please leave us a review. And you're not going to want to miss next week's episode. We are talking about the cure to fast fashion. I'm going to let listener Caitlyn Luitjens take us out with one final note about the collective power of plant-based eating.

Although I can't change the entire meat production industry, I can change the demand side of it, even if it's just myself reducing demand slowly, and hopefully others catch on as well.