Can We Overcome Overconsumption?

How do we deconsume in a consumerist world? When we buy less, we save money, cut down on clutter, and lower our emissions. And this collective shift has another big impact — helping us to steer the economy away from disposable, poorly made products, and dangerous supply chains. Becoming more conscious consumers is a pivotal step in building a more sustainable economy.

On this episode, you'll hear:

- How many returns end up in landfilss each year.

- How people around the world think about overconsumption, and how they're deconsuming in their own lives.

- Lauren Bash shares how we can take care of what we already have. Lauren Bash talks about her mom's new Tool Library, visiting a Repair Cafe, and her love of Buy Nothing groups and bulky furniture day.

- Sanchali Seth Pal talk about how much more folks are overconusming in wealthier countries, and the cost of this overconsumption.

Find Second Nature wherever you listen to podcasts: Spotify | Apple Podcasts

Here are some of the people you'll hear from in this episode:

Citations and further reading

Citations:

- We’re gobbling up the Earth’s resources at an unsustainable rate, UNEP,

- Worldbank, population

- Optoro, 2022 Impact Report

- Free Public Data Set - Global Footprint Network

- How many Earths? How many countries? - Earth Overshoot Day

- Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI)

- Most Americans Have a Monthly Budget, but Many Still Overspend - NerdWallet

- More Than A Third Of Americans Rent a Self Storage Unit - Real Estate Investing Today

- Impulse Buying: Why We Do It and How to Stop - Ramsey

- 2023 Commons Community Impact Report

- Per capita CO₂ emissions, 2022

Further reading:

- Microtrends, Ultra-Fast Fashion, and the Overconsumption Cycle

- How Fast Fashion Brands Are Fueling Your Shopping Addiction

- Intention Over Impulse: 6 Tips to Avoid Overconsumption When Shopping Online

Episode credits

- Listener contributions: Alyssa Barber, Amea Wadsworth, Andrea Reno, Caitlyn Luitjens, Daria Panova, Jonas Schäfer, Mac Hansen, Madeline Streilein, Nicole Collins, Rachel Orenstein, Timmin Vooijs, Willa Stoutenbeek

- Featuring: Lauren Bash and Sanchali Seth Pal

- Editing and engineer: Evan Goodchild

- Hosting and production: Katelan Cunningham

{{cta-join2}}

Full Transcript

Katelan: Hey. Welcome back to Second Nature, the podcast from commons where we talk to people about how they're living sustainably in an unsustainable world. When listeners submit to the show, one of the questions that we ask them is, what is your biggest climate concern? And so far, the top response has been overconsumption. I'm concerned deeply about the overconsumption.

Daria: I think it's a huge problem here in the States and probably across the globe too. It has become a part of the culture now.

Alyssa: Overconsumption makes me worry about our ability to collectively agree on something that would be better for our wallets, mind, and planet. Yeah. It became very dystopian.

Timmin: The fact that we're just spending all of our free time looking for new things to buy. And I guess something just clicked, and I was like, that's so weird.

Katelan: When we talk about overconsumption, we're not talking about, like, that one pint of Haagen Dazs that you get with their weekly groceries or buying your kid a winter coat to replace the one that they've outgrown. We're talking about lots of excess stuff that we buy and don't really need or in some cases, don't even actually want. Overconsumption is this sort of meta climate issue that touches so many other things like fast fashion, food waste, plastic waste, Amazon.

Deconsuming in a consumerist world means going against the norm. But with enough of us doing it, we can change the norm altogether. Mari Kopeni is a young activist in Flint, Michigan. You may know her as Little Miss Flint. She says it's time to shift from being consumers to caretakers.

Today, we're gonna talk about what it takes to start making that shift happen. I'm your host, Katelan Cunningham. And on this episode of second nature, we're reckoning with the relentless allure of consumer culture and hearing firsthand deconsumption tips and strategies from listeners. I'm gonna chat with Centrali St. Paul about the environmental impact of all this consumption and ask her who's buying all this stuff?

Plus, I'm talking to climate storyteller and activist Lauren Bash about Buy Nothing groups, repair cafes, and her own deconsumption journey. Let's go. Once you start looking for opportunities to over consume, you see them everywhere. Stores promoting cheap items in the checkout aisle, a new big sale event every single month, and you can most definitely find it on your TikTok and Instagram feeds. Stop.

Tiktok clips:

- If you are a person that's still looking for a gift to get a hardworking man or woman, this fliptub is like no other fliptub. If someone would have told me I'd be buying furniture from TikTok a couple other foot tub.

- If someone would have told me I'd be buying furniture from TikTok a couple months ago, I wouldn't believe them.

- Make sure you place your order if you've been wanting to get an ice maker. You will not see a better deal on these you homies.

- I got the Viral Mop, which saves me time by separating the clean and dirty water so I don't have to change out the water so often. How do I get the deal? Someone asked. Great question. Just go ahead and add it to your cart.

Tapping through these TikTok ads, it becomes dangerously easy to forget that every part of everything that we buy from the batteries in our phones to the shoelaces in our shoes are made from natural resources, and we're using up these natural resources at a record pace. Since 1970, the global population has increased 115%. That's slightly more than doubled, but our resource extraction has tripled. So we're making more stuff and we're buying more stuff, but are we using more stuff? I'm not so sure because we're returning a lot of it.

In 2022, folks in the US returned over $800,000,000,000 worth of merchandise, and transporting these returns back to warehouses created 24,000,000 metric tons of emissions. That's more than the emissions of 5,000,000 cars driven for a year, just in moving returns around. What's even more alarming and depressing is that a lot of these returns aren't even resold. In 2022, 9.5 billion of items returned in the US ended up in landfills. Now don't get me wrong.

It is company's responsibility to properly handle these returns, and a lot of them are failing at it. But seeing all these unwanted or unneeded items piling up in landfills, it's a real life spectacle showing us how overconsumption adds up really quickly. When listeners shared their overconsumption struggles, a few key themes arose. Maybe these will resonate with you. Spending too much money on too much stuff, then running out of space for all that stuff, and feeling guilty about throwing the stuff away.

“How can I buy less stuff when stuff makes me so happy?” Listener montage

Rachel: How can I buy less stuff when stuff makes me so happy? I totally understand this question. So I would say that the reason why stuff makes you so happy is because there's also a very big business around making you think you need stuff. If you are trying to buy less, I offer one mantra to evaluate a purchase. I like this, but why do I want it?

Caitlin: Is it worth me supporting this company? Is it worth increasing my carbon footprint? The process of thinking about price is not just dollars and and cash that you can see in your hand, but there's many other costs to consider.

Rachel: The newness fades. That is not to say that you should shame self out of buying something that makes you happy, just that you should reconsider whether the joy an item sparks is temporary or if it really will add value to your life.

Amea: I think that if the idea of a no buy or low buy year feels intimidating to you, that is a sign that it would be very good for you. I'm about a month and a half into mine, and it has been very good for me. I've been tracking everything I spend, but I've also been tracking my consumerist impulses. Like when I feel like, oh, I really would like a new bag or I wanna buy this and I wanna buy that. And I've been writing them down.

And I've noticed that as I've gone on, I felt these consumerist urges less. Do I have any tips for people who are trying to buy less? It's kind of like a mindset switch.

Mac: Not buying temporary things is what makes me happy and usually that means you buy a lot less.

Madeline: So I remember in 8th grade campaigning my parents to instead of buying the $20 backpack that we got each year that was, like, broken by the end of the year, to get $180 North Face backpack that I promised to use all 4 years because I was confident that it would last.

Nicole: Look at your bank account. As a college student, I don't really have a lot of money to just spend on random things. So that helps me with saying no to a lot of unnecessary purchases. I'm really proud of, like, t shirts that get holes in them. I can cut them up and make them into rags once it's like, hey, man, you should be wearing that in public.

Rachel: So much anxiety and uncertainty in the world, and it's easy to make ourselves feel better just for a moment by buying stuff. Soon enough, it becomes clutter, just another source of anxiety. And then there's the guilt of spending money and the guilt of contributing to consumerism and the guilt of knowing this purchase will not bring you happiness. Of course, it won't. Necessities are important.

A dry roof and a warm belly are conducive to happiness. That is true. But anything more than that, and you do risk losing sight of what actually makes you

Interview with Lauren Bash

Katelan: Of course, ads are a big source of overconsumption. They create the artificial scarcity of a sale or the novelty of an item makes us feel like we need something that we didn't even know existed 5 minutes ago. There are also moments in our lives that prompt us to buy things when we don't necessarily need them.

It can be helpful to identify those triggers for yourself, like social events are a big one, getting a new outfit for party or wedding. Trips and holidays can also make us feel like we wanna buy new stuff. Even adopting a new hobby can make us wanna buy new things. Another big one is moving. Lauren Bash is a storyteller and climate activist, and, coincidentally, she just moved.

I met up with her at her new place in LA to talk about overcoming overconsumption.

Lauren: Hi.

Katelan: Thanks for coming on the show.

Lauren: Of course. Thank you for having me.

Katelan: So I wanted to start with this series that you've been doing on Instagram and TikTok, where you use what you have for as long as possible. I wanted to know what prompted you to start that series and, like, were there any objects in your life that you started with? Yeah.

Lauren: So my mom is building a tool library right now in Compton. And it's a facility where folks can come and borrow tools to maintain their house, or start a business, or things like that. And every time I went, I'm like, this seems so obvious. Like, of course, you don't need a lawnmower if it's going to sit unused for 99% of its life.

But if there was one that the community could use, and then everyone could mow their lawns. I feel like lawnmows are a bad example as, like, a climate activist, because we shouldn't have lawns. But, like, let's say a wee wacker or, like, a, ice trimmer. Shovel. Yeah.

But if you only need it for the couple hours a year or month that you're using it, it instead could be a shared resource for the community. And so I've just been witnessing her build this tool library, it's been so cool. And one of the programs they host is a repair cafe. And it's nothing new.

It's been going on for, like, decades. And it's just people come together and they volunteer their time. There's a few makers who are kind of in charge of it, and you would bring something like a broken toaster, a broken pair of shoes, or something, and the makers there will help you repair it.

It's super cool. So I think I just kinda looked around my house and did an audit and was like, wow. I have so many things already in my life, but I think the difference between my generation and my mom's generation is that ours is quick to replace something when it's broken instead of repair it. And part of that too is because I think things made now aren't made to last. You know, they're made with cheaper materials that just generally break down quicker.

Yeah. Whereas, I don't know if I looked at, like, the clothes in my grandma's closet, I'm like, wow. You could literally wear this for a 100 years. Hence, why vintage clothing is made so well, because it's made to last forever. Yeah.

So that's where that came from. And I just just looking around my life and my house and thinking of all the things that I could take care of instead of replace. And this yearning that I think a lot of millennials and Gen z folks have too to kinda go back to how our grandparents and parents were living too.

Katelan: As a climate communicator, you are on social media a lot. You publish a lot of content on socials.

So I wonder what it feels like, like, publishing your often, like, deconsumption message in this space that's often trying to, like, sell us things. Like, what it feels like to you, how that's evolved your brand, and, like, how you've built community in that space.

Lauren: It's so cool to see the shift in conversation. I think even, like, outside of climate minded people of overconsumption just being, like, a huge conflict of our generation. And I think when you see these massive corporations like the Shein or the Amazon's, and you just see how much is being produced on a daily basis or shipped or delivered on a daily basis.

And my mom said something that was so wise the other day. She says, every time you look at something, you can see the natural resource that was required to make this. So if it's a piece of clothing, whether it's synthetic or natural fibers, like, where was that source from? What part of the Earth did it come from? How many hands touched it before it got to you?

And just being extremely mindful of that and the natural resource required.

Katelan: There's, like, a section of Braiding Sweetgrass. I don't know if you've read that.

Lauren: Every year every April, I listen to her.

It's so it's so good. Listening to the audio is like I know. It's 17 hours, but it's worth every minute.

Katelan: But she has that whole section where she's looking at her desk or, like, through her pantry, and she's like, and this came from this and

Lauren: Yes. And she has a really hard time with her pen.

She's like, I can say thank you to the oak that made this table, and I can say thank you to the bees who made this candle. But when I look at my plastic pen, I have a really hard time because we're so disconnected from the fossil fuels that made this petrochemical that made this plastic. Yeah. And so now, when you go into, like, I don't know, I always get the heebie jeebies in, like, a Costco, like a big box store, when you, like, look at how many natural resources were required to make these things. And I think that mindset or even just, like, that thought is, like, making its way onto the Internet too.

And so, yeah, on Instagram, I remember when Instagram changed the, notifications button to the shop button, and it was kind of like, oh, yeah. Remember that this is a commercial platform that is being used to sell us stuff. And then obviously TikTok has their whole, like, TikTok shop feature. So there is plenty of consumption being done on both apps. But I think it's really inspiring and really exciting and, like, fulfilling to see so many people talking about overconsumption and what we can do on an individual level and, like, on a macro level when we collectively speak about this to say, like, woah, this has kind of gotten on hand.

Katelan: A lot of folks have practiced, like, no buy periods. Yeah. I'm doing one right now just with clothes. Yeah, clothes for the year. But I wonder, like, in the world of deconsumption, how do we still have our little treats? Like, how do we how do we allow ourselves something fun without indulging in, like, the over consumption piece of it?

Lauren: I think it's fine to have a desire to want something, but now I have a notes in my phone when I want something. And it's not only clothes. It's, like, I mean, honestly, I wanted an air wrap for a while. The Dyson air wrap. I was like, wow.

People are curling their hair, and it looks so nice. I had it on there for a while. And then when I got my hair dryer fixed, I was like, oh, I don't need it. I can just get a round brush and, like, learn the other way. I will say, even putting in your notes and just being patient, I feel like the universe is so rad sometimes, and someone will, like, give you something.

Or you'll, like, see it at a garage sale. I'm like, wow. Patience. Yes. This is why we wait.

Katelan: Yeah. That's happened to me in my Buy Nothing group too. More with, like, really practical things, but I'll be like, you know what? I really need a new pot for this plant, and it'll be like in 2 weeks, and there's the perfect pot

And I'm like, I knew I knew I should've waited. This is great.

Lauren: The buy nothing groups are it. I feel like buy nothing groups are the future. Just people — it's the same concept we were talking about with the tool library too, is you're like, hey, I can't see my house, I need a ladder, I don't have a ladder.

Mhmm. And someone's like, I got like 4 in my garage. And I'm like, oh, this is it. I wonder if we have, like, a false sense of urgency because we can get it so fast. And it's like, we once didn't have this, and we were fine.

Katelan: Like, we grew up without this. Yes. Yes. What did we do before we could just buy any cord we needed on Amazon?

Lauren: I know. I think the one that gets used about that a lot is how things were once refillable before plastic was around because every there was no such thing as, like, disposability. Mhmm. So my mom talked about, like I mean, I feel like everyone talks about the milk delivery and how it was glass jars, but my mom was like, that's how everything was in the grocery store. Like, you would bring the bags back. There was no plastic on the produce.

All the produce was ugly. You would buy things in bulk because that's how they were sold. Yeah.

Katelan: Like, there's a piece of overconsumption that we're sort of responsible for.

Like, we can stop buying that stuff. Yeah. But, also, you know, a lot of places don't have refill stores and, like, they're the pieces that we can do, and that feels the packaging piece feels like a piece of overconsumption that is, like I mean, there's many of it. A lot of it is the company's responsibility for sure, but that one's so prevalent because it's, like, that puts a responsibility on us, the consumer, just because we needed to buy laundry detergent. Now I have to figure out what to do with this.

Lauren: Yes. It's too it's too much. These corporations have so much money. They could figure out refill programs. Yeah.

They could do it. Like, Target could be a refill store. Mhmm.

Katelan: Or even, like, a baby step would be, like, go from plastic to aluminum. Like I know.

Lauren: Yeah. In every area of LA I've lived in, there's always been folks who come and look through the recycling bins. Yeah. Because that's money you paid for that.

You paid 5¢ a bottle or a can, and that's about you've throwing away cash. Yeah. You're not taking it to a recycling center. Yeah. So if we made waste valuable and probably even a little bit more valuable where it wasn't just folks going through recycling cans, but we actually had to go exchange it Yeah.

Yeah, I think you'd see everything change. Yeah.

Katelan: So we have these moments in our lives that sort of trigger us to over consume. I think the holidays is a really big one. Another one is, like, moving or buying a house, which you've just done.

Moved into a new place. Have you had any feeling of wanting to over consume, or how did you sort of brace your expectations for that?

Lauren: I love that we're in my living room right now because I feel like I get to brag. Like, there's this thing called bulky trash day Yes. In my hometown.

It's in, like, the wealthier part of town, but it's where all these wealthy people put their bulky trash on the curb because they don't wanna take it to a thrift store or something like that. But we it's twice a year. My sisters and my mom and I go every year and, like, go through these rich people's trash because it's, like, amazing stuff. So this chair. This piece of art, this lamp, and this dining table were all things that people put on the tracks, on the curb.

I could not believe that. That's incredible. Yeah. That's it from in this room. Wow.

This is our first time owning a house, which is awesome. And the renovation it's so tempting to just wanna do something really fast so it's done. My bathroom was just, like, a disaster when we moved in. And I was like, oh, I just want to take care of it. But I'm learning that the home renovation is similar to, like, the fast furniture, industry, I guess.

I mean, like, I just want to buy something really quick, so it's a so we have a couch. Yeah. And you can do the same thing when you're renovating your house. I just want to get, like, a vanity that's just really cheap that I can put in here, so I have a nice sink, so I don't have this, like, crappy sink, or I want to put, like, adhesive floor tiles down, so it covers it up, because this is so ugly. Or cheap light fixtures, or whatever.

And I'm like, wow, it's the same thing with house renovations. Like, take your time, source these things, do it right, because you want this to last. So we have several listener questions that I thought might be good for you. Cool.

Katelan: We have a question from Andrea in Italy, and they asked, how can we be as circular as possible around our households?

Lauren: I think it was back to we're talking about our older our our grandparents' generation. Mhmm. My grandparents are from Argentina, and they reused everything in our house. Oh, my gosh.

Like, a glass jar is like a hot commodity in the house. Right? Because it serves so many different functions. My uncle in Argentina has a garden on the roof of his office building. And it's, like, looks kind of junky when you first look at it, but it's because they reuse everything.

Like, the coffee tins and the yogurt containers and, like, like, file cabinet. Like, everything is reused. And so I think being circular in the home is just saying everything could have a second life, if not like an infinite life, if we if we choose to. And then, like what we said earlier, it's just preparing your stuff to make it last as long as possible. That's just keeping it in the cycle.

Even if you're not gonna keep it, like, okay, I'm gonna fix this chair. I'm not gonna use this chair anymore, but I could put on Buy Nothing Group and someone else use this chair. Yeah.

Katelan: That's really nice. I love the idea of fixing something even if you're gonna get rid of it.

Lauren: Yeah. Yeah. We have, we like a non like an open space instead of the coffee table, but the coffee table we have needs some love. And I'm like, oh, I can't wait to, like, fix it up and then put it on Facebook Marketplace.

Katelan: So we have one question from Jonas in Germany, and they asked, “How can I fight climate change without getting too involved and burnout or overstress?”

Lauren: I'm a big advocate for community.

The way I joined the climate movement was by joining a local chapter of a grassroots climate organization called the Surfrider Foundation, and we have a 150 chapters across the country, which includes our student clubs. Mhmm. And they've been the way I refill my hope tank. Western Individualization has us thinking that it's our fault and our responsibility, and that's what makes us feel overwhelmed and powerless. But when we plug into community, there are so many brilliant people within these chapters or organizations or community groups who are, like, experts on different things.

That is what gives me hope. And I think the burnout comes from trying to do too much on your own with the thought that you can't take a break. But when you're in community, I think it's Sunrise Movement that says, take a nap and come back tomorrow. You don't have to do this alone. And I think they sing it.

Only in community will you have that that space to rest and then come back. Love that advice.

Katelan: Thank you so much for being on the show.

Lauren: Yes. Thank you for having me. This is lovely.

What Happens if We Get This Right, with Sanchali Seth Pal

Katelan: When we hear about the environmental toll of something like overconsumption or fossil fuels or fast fashion, it's easy to detach ourselves from it. It's easy to forget that humans are part of the environment too. I wanted to ask Commons founder Sanchali Seth Pal —what is the human cost of this overconsumption? Who's doing all this overconsuming, and what happens if we start deconsuming on a large scale?

Katelan: Welcome back.

Sanchali: Great to be back.

Katelan: Okay. So we know that folks in richer countries are consuming way more than people around the world, but I wanted to know exactly how much more.

Sanchali: Okay. So if everyone in the world lived like we do in the US, we'd actually need over 5 Earths to sustain us. European countries are doing a little better. If everyone lived like British people or Swiss people or Portuguese people, we'd need, like, 2 or 3 earths.

But mostly, the developed world is operating in Earth debt. And richer countries are putting us in the greatest debt.

Katelan: Earth debt. I've never heard this phrase before. What what is Earth debt?

Sanchali: Okay. I kinda made this phrase up, but I'm using it to describe the fact that people in wealthier countries are using more resources per person than the Earth can sustain. So we're using more than the resources that are within our means. Okay. That makes sense to me.

And this is causing the worst effects for people who live in poorer countries. For instance, if we all lived like the average person in India, we'd actually only use 80% of the resources that the Earth can offer. So people in India are living within the Earth's resources. But then also people who live in poorer countries are at the greatest risk of climate disaster and climate vulnerability. So according to the Climate Risk Index, India is one of the 5 countries in the world at the greatest risk of climate disaster.

Katelan: What makes a country more at risk of a climate disaster?

Sanchali: In general, people who live in poorer countries have fewer resources and less resilience to adapt in a case of climate disaster, making their people the most vulnerable to to its effects, especially to death, disease, and destruction. That means that while the climate crisis is being disproportionately caused by wealthier folks, unfortunately, it's gonna devastate poor folks and people in poor countries first.

Katelan: Okay. So when we talk about wealthier folks, are we talking about, like, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk?

Sanchali: Definitely talking about Jeff and Elon. Don't get me wrong. But it's actually more of us than just the 2 of them. In the US, if your household makes over $61,000 a year, that puts you in the top 10% of households by global wealth just because the US is a wealthier country than most other countries. Mhmm.

And Oxfam did some recent research on carbon inequality, and they found that the richest 10% of households in the world are responsible for 30% of the total increase in human caused emissions in the last 15 years. So that means that if your household is making over $61,000 a year, your choices have disproportionately more environmental impact than most peoples in the world.

Katelan: That's a lot of households in the US because that's below the median household income of of folks living in the US. That's really shocking. So how does this overconsumption physically show up in our lives and in other people's lives?

Sanchali: I think we can all relate to the idea of overconsumption, and in our own lives, it's not great. We feel it when we're seeing ads. And there's a ton of pressure to overbuy. So 84% of people in America are overspending on their budgets, and our credit card debt is at an all time high. Yeah.

Katelan: I know a lot of people are feeling it. Where where are we putting all of this stuff that we're buying?

Sanchali: We're putting it in our homes. We're cluttering our homes. We're stuffing our closets.

We're even buying storage units, and even that benefits companies. 21% of Americans now pay for a storage unit. What are we putting in all of these storage units and all these closets? What is what are we buying that's taking us over the edge of our budgets? I mean, sometimes it's stuff we think we need, but we don't.

But honestly, it's often a lot of impulse purchases. And impulse buys have been on the rise since the pandemic. So according to research from Ramsey, impulse purchases have increased 72% since 2020. That's about $314 a month for the average American or 9% of our total monthly spending. That's shocking.

Katelan: That is a lot of money.

Sanchali: Yeah. It is. And we take a look at some of our data from Commons to try to think through, like, what kind of impact would this have if people impulse bought less. And we found that if Americans cut down our impulse purchases by about 75%, we'd lower our annual footprints by 3% and save $2,800 a year.

Katelan: Wow. Almost $3,000 a year. That sounds super impressive to me. But that 3% emissions, I'm gonna be honest, that doesn't sound as impressive.

Sanchali: Yeah. Okay. So 3% doesn't sound very big, but this actually gets to what we talked about earlier. Even small changes for people with high incomes can make a really big difference. So an American cutting their footprint by 3% is about 450 kilograms of c 02 or 25% of the annual emissions of a person in India. Okay.

Katelan: This is clicking for me now. So reducing overconsumption, say, through our impulse buys, is not just good for us. It's good for other people around the world too.

Sanchali: Absolutely. We save money.

We save space in our homes. We feel better. But it's not just benefits for us. We're all connected. We're all breathing the same air and using the same atmosphere with the same amount of atmospheric carbon.

So buying more thoughtfully and buying less in our own lives can have a really positive ripple effect on others all over the world.

Katelan: I'm excited. I think we can do it.

Sanchali: We can save money and also feel great about it. Amazing.

Katelan: Thank you.

Katelan:

I think one of the greatest antidotes to overconsumption is just having gratitude. Because consumerism needs you to think that you need something you don't have or that you're one product away from a perfect home or a perfect wardrobe or a perfect lifestyle. But when we realize and appreciate what we already have and the resources of our communities, maybe, hopefully, we can break free from that pull of overconsumption and save a ton of money, time, and emissions while we're at it.

Thanks to our listeners who shared their over consumption experiences and invaluable advice. This show is nothing without community, and we'd love to hear from you for season 2. Go to the commons.earth/podcast to tell us about your sustainable life. On this episode, you heard from Alyssa Barber, Amea Wadsworth, Andrea Reno, Caitlyn Luitjens, Daria Panova, Jonas Schäfer, Mac Hansen, Madeline Streilein, Nicole Collins, Rachel Orenstein, Timmin Vooijs, Willa Stoutenbeek

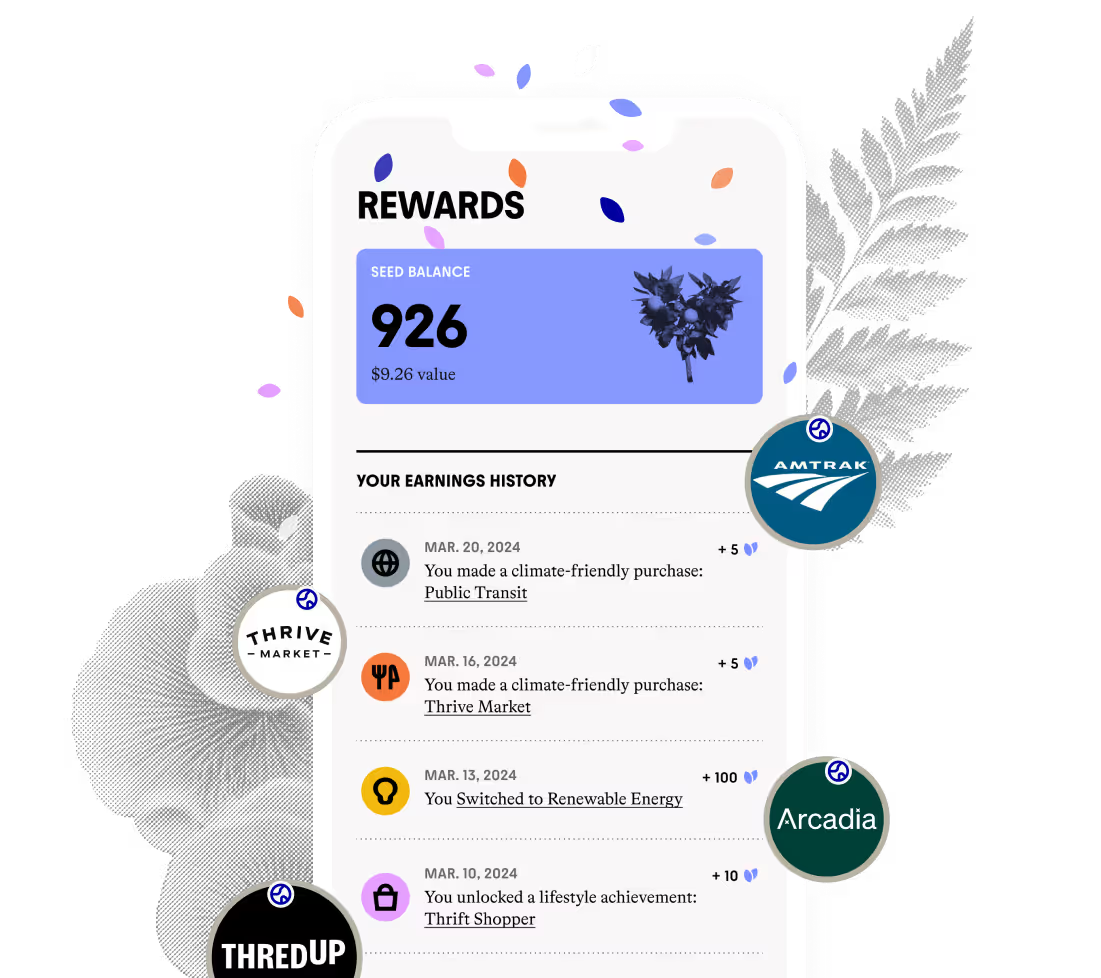

A great way to cut down on overconsumption is to get a handle on what you're consuming. What if you had a sustainable spending buddy that helped you track the emissions of every purchase and give you personalized tips to be a more conscious consumer. That's what the commons app is for. When you download the app now, you can join the June collective challenge and earn rewards every time you take sustainable transit. Go to the commons.earth/secondnature to join the app. Our editor and engineer on this episode was Evan Goodchild.

It was fact checked by Commons Carbon Strategy Manager, Sophie Janeski. It was written and produced by me, Caitlin Cunningham. For more stories from our community, join us on Instagram. Follow the show at second nature earth. And head to the show notes for citations and further reading.

Next week is all about compost. We're talking food waste, worms, and methane. Until then, I'll leave you with these final words from listener Timmin in Amsterdam.

Timmin: I feel great being a conscious consumer and trying to under consume just makes you feel good. I guess you feel bound to this group and you get some sort of status out of being someone that is sort of going against the system.

So, yeah, consuming less and buying less is awesome because you feel like, yeah, I'm I'm having a good impact on the world, and, that is prices.

Find Second Nature wherever you listen to podcasts: Spotify | Apple Podcasts