Skip the Greenwashing: What to Look for in Sustainable Fashion

.avif)

When you’re trying to live more sustainably, fashion can be hard to navigate. The industry is ripe with greenwashing that masks exploitative practices for people and planet. But sustainable fashion is an expansive, exciting world of circularity, repair, and trustworthy, responsible brands.

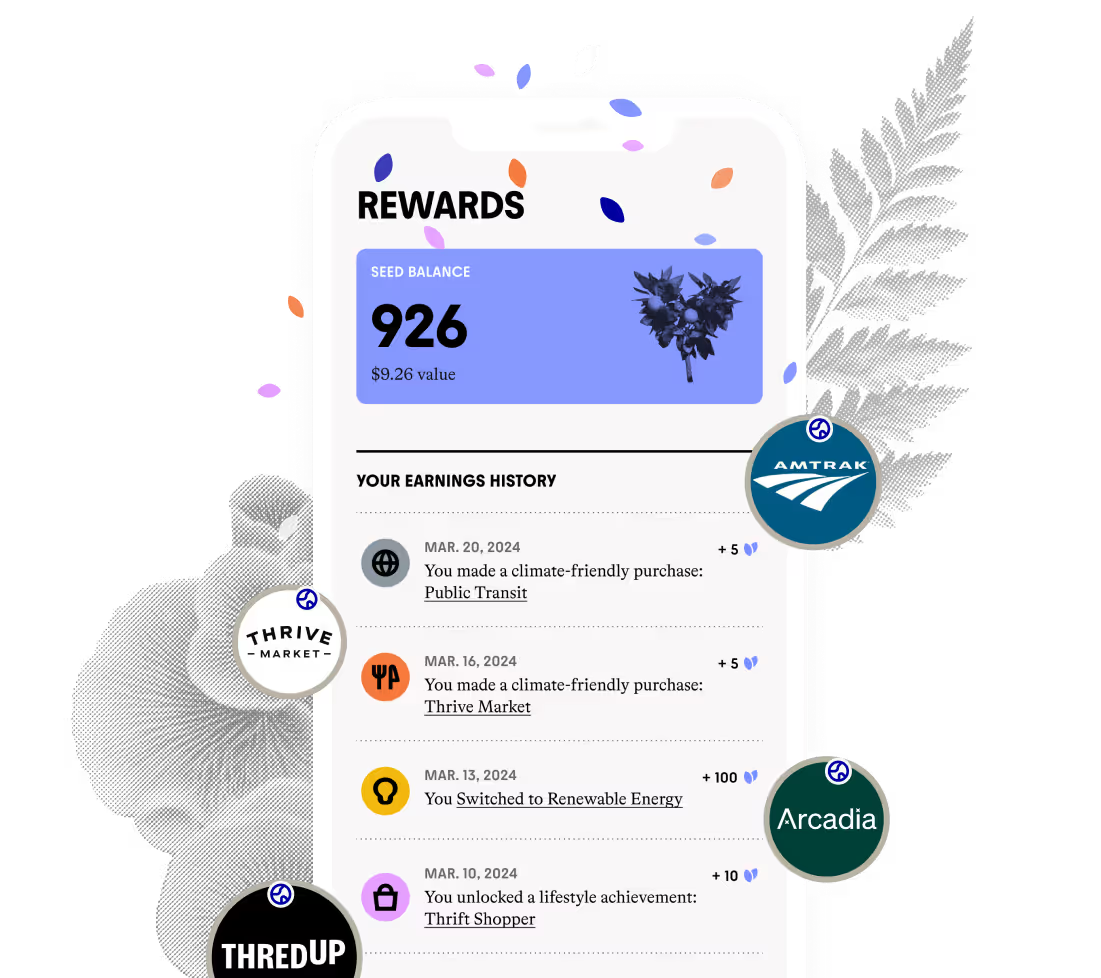

On this episode (our season 2 finale!), we’re coming face-to-face with the cost conversation when it comes to sustainable fashion, getting real about overconsumption, envisioning a practical future for the industry with fashion expert Samata Pattinson, and finding out what sustainable fashion means to you. Plus, we’re talking to Commons’ Carbon Strategy Manager Sophie Janaskie about what to look for in a sustainable brand.

➡️ If you’re struggling to find sustainable fashion brands that you can trust, we got you. The Commons team has researched and rated hundreds of fashion brands so you can skip the greenwashing. Check it out here.

Here are some of the people you'll hear from in this episode:

Episode Credits

- Listener contributions: Alexa Rivera, Cindy, Danielle Bird, Faith Winston, Liv, Obehi Ehimen, Verity

- Editing and engineer: Evan Goodchild

- Hosting and production: Katelan Cunningham

{{cta-join2}}

Citations and Further Reading

- Shein's Average Shopper Spends $100 a Month on Clothes, Considers Herself Environmentally Conscious, Business Insider

- Fashionopolis : Dana Thomas : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming, Internet Archive

- Textiles: Material-Specific Data, US EPA

- Fashion on climate, McKinsey

Full Transcript

Katelan (00:00):

Hi, welcome back to Second Nature, a podcast from Commons.

Katelan (00:09):

Our team at Commons just launched a new tool that we're really excited to share with you. We have evaluated, reviewed and rated hundreds of fashion brands so you can skip the greenwashing and find brands that you can actually trust. You'll also find great tips to care for your clothes and to get some de consumption guidance along the way. If you wanna try it out, just go to the Commons Earth. You can use this tool to search brands in your closet and see how they stack up or discover sustainable brands that you've never even heard of. At Commons, we're all about making it easy to find the most sustainable options for your life. And on this show, we talk to people to find out how they're living sustainably in an unsustainable world.

Katelan (00:58):

Since the eighties, we're spending half as much money on clothes, but we're buying five times more. The decrease in the cost of clothes, along with the increase in quantity is a direct result of the boom of fast fashion. Fast fashion. Brands have gotten really good at convincing us that we need new clothes all the time, and they make them so cheap that it can be really hard to resist, but resist, we must, because behind that low price tag, a lot of corners are being cut in the form of dollars and workers' paychecks, safety and factories and wasteful plastic materials. Just to name a few glaring issues. When we talk about sustainable fashion, skipping fast fashion is definitely part of that. We did a whole episode on that last season. It's a great companion to this one. I

Speaker 2 (01:48):

Would go absolutely nuts over it. The worst part is that there are some clothes that I literally have never worn.

Speaker 3 (01:55):

So just kind of having to rewire my brain to be very creative with what I already have. And you know, I realized that I already have so much I can play around with it so much, I just need to open my mind more. It's such a

Speaker 4 (02:08):

Growing problem and it's growing in such a fast pace and um, I don't wanna take part in that system.

Katelan (02:24):

When we think a little bigger, sustainable fashion requires us to change how we think about our clothes and how we participate in the fashion industry. It requires us to deprogram ourselves a little bit, to hop off the trend hamster wheel care for our stuff a little bit longer, pick secondhand first and choose better brands when we buy new stuff. That's what this episode is all about. I'm Katelan Cunningham, and today on Second Nature, we're gonna find out what sustainable fashion looks like to you. We're going to envision the future of sustainable fashion with Advocate and Black Pearl, CEO, Samata Pattinson, and we're talking to Common's very own carbon strategy manager, Sophie Janaskie, about how you can tell if a fashion brand is actually sustainable. Here we go.

Katelan (03:16):

I'm gonna start by addressing the elephant in the room of sustainable fashion. If you wanna start choosing more sustainable fashion, one of the first things that you might be worried about is cost. And I totally hear you. You can get a pair of jeans from some fast fashion brands for as low as 30 bucks, but at more sustainable brands, you might be paying three times that amount. But hear me out, A sustainable fashion journey doesn't need to mean that you spend more money on clothes. Instead, for most of us, it has to start with being really, really real with ourselves about the amount of clothes that we're buying in the first place.

Katelan (03:57):

Fast fashion brands expect you to fill your cart with a bunch of cheap items. In fact, their whole business model is banking on it. And there's actually some psychology behind this. When we like an item, our brain compares the pleasure of having it to the pain of paying for it. So the lower the cost, the lower the pain, and the lower the pain, the less pleasure we need to justify the cost. It's a concept called transactional utility, and it comes down to the idea that if something is cheap, we don't have to love it that much to convince ourselves to buy it. This my friends, is fast fashion's sweet spot. Like Zara knows that even if you're only gonna wear a shirt once, you'll convince yourself to buy it because it's on sale for 12 bucks. Shein knows that micro trends are not gonna last more than a month, but they can get you to buy that trendy skirt for the low, low cost of five bucks. Our brains actually get joy from a great deal, but with fast fashion that joy often fades pretty quickly. Again, these companies are counting on it. They make a big business out of getting you back in the door to buy more stuff with their next sale. In the sensory delight of all the new styles and new colors and new textures, all that brain stimulation can override the fact that you maybe probably already have a lot of clothes.

Katelan (05:21):

On average, Americans buy a new item of clothing every single week. The average Shein shopper spends a hundred dollars per month on women's clothing, despite the fact that we're buying way more clothes than we used to, there are still just 365 days in a year to wear these clothes with modest closets to store them. So we purge our wardrobes and send a lot of clothes to landfills or donate them. We're even donating too many clothes in the us. Less than 15% of discarded clothes get recycled. In 2018, we sent a whopping 11 million pounds of textile waste to landfills. It's like we're literally being buried in clothes. In my vision of a sustainable fashion future, we are mending and upcycling our clothes to wear them for longer. We're only buying stuff we really love, either secondhand or from brands that aren't doing harm to the planet. But of course, I wanted to hear from you, what does sustainable fashion look like to you?

Liv (06:27):

Sustainable fashion is slow and is reputable and is recyclable and is basically keeping garments as long as we can.

Verity (06:42):

Sustainable fashion to me is circular fashion. So it can be put back into our environment and either like, you know, biodegraded or made into something else and then keep going so then there's no end to the life where it's just gonna sit in landfill forever.

Cindy (06:58):

I see sustainable fashion as clothing pieces that are either produced in a way that respects and pays workers at a livable wage and also doesn't harm any animals and also doesn't harm the planet.

Danielle (07:17):

It's also about being anti-fat, fashion and anti over consumption. And by that I mean not buying from sheen, for example, but actively trying to raise awareness, encourage people not to buy from fast fashion outlets. .

Faith (07:30):

What I look for in a sustainable fashion brand, I look beyond the surface. A brand that not only creates, but also gives back transparency is essential. Knowing the story behind the craftsmanship quality and craftsmanship holds a deep meaning to me.

Alexa (07:47):

I definitely, number one, look to see if their production is ethical, but most importantly I look to see if their fabrics and materials are high quality and sustainable. When something is high quality and durable, it will last you a long time and can help reduce your overall clothing consumption.

Obehi (08:08):

I like to kind of just take my time really when buying a new item and really doing my research, learning how to take care and maintain my clothes, which can mean going to a local tailor that I have or really spending the time to really look at the laundry instructions tag.

Verity (08:31):

I do think natural fibers are very important because they bio degrade and make it circular, but at the same time they're very expensive. And being part of the textile world as a textile designer, I know quite a lot of stuff about natural fibers and it takes so long to just make like one item. So you can't really price it for something that it's not worth. So it's uh, difficult subject that one. But yeah,

Faith (08:58):

I'm inspired by brands like fabrics turning waste fabrics into textile bricks and the OR foundation who advocates for environmental justice. I remember I recalled seeing the impact of textile waste in Ghana. There was mountains of discard clothing and it's not just there. It's such a, like a global issue, yet there is hope of those who upcycle and find new purpose in what others have thrown away.

Obehi (09:27):

In my stable journey, I realized that taking it slow is key rather than doing everything at once, becoming overwhelmed and then quitting altogether. I think taking small steps in this journey is it's just so much more sustainable ironically, rather than just replacing everything you have and just going full force with it all at once. You know, it could be quiet draining, but taking one step at a time is definitely best. I feel.

Katelan (10:03):

Our team here at Commons, we have reviewed hundreds of brands sustainability efforts, and we have found that most of the big fashion brands out there, they're fast fashion. Like if you buy clothes at a mall, it's probably fast fashion. It's truly shocking, honestly depressing. It feels like a betrayal because these big brands, they have the money and resources to provide safe working conditions and fair pay and use low carbon energy and materials, but they're not. And what's worse is that many of them are greenwashing and they're lying to make it sound like they're doing enough. There are some really great fashion brands out there doing the work to create more sustainable supply chains and encourage more conscious consumption. But still, I wondered what's the role of sustainable fashion brands in a world that already has enough clothes? That's one of the questions that I wanted to ask. Somato Pattinson, she's a sustainable fashion advocate and the CEO of Black Pearl, which is an organization at the forefront of cultural sustainability. You may have seen some of Sam's eco-conscious styling on the Oscar's red carpet. Hi Sam, thank you so much for coming on the show.

Samata (11:19):

Thank you for having me.

Katelan (11:21):

You spoke at our event in April and you talked about going back to visit your family in Ghana and realizing that these things that you grew up with were very sustainable, but in fashion there's this idea of kind of repackaging or rebranding this old idea into something new and something flashy, which of course is very fashionable too, right? Like we're living in the early two thousands again in fashion. And so I was wondering, what does it look like to you if fashion starts to maybe detach from that newness in order to tap into historical or cultural, more sustainable practices in fashion?

Samata (11:55):

This is such a good question, and I think one of the first things that potentially that looks like is taking away the stigma of old. Hmm. And that's not just something that I think is linked to fashion. I feel like it's linked to so many things, like there's a kind of discrimination against age, the idea of getting older, being undesirable, or there's a discrimination against things being used and the implication for so many people that that means that they're dirty. Like there are so many ways that new and old like almost need to swap for a

Katelan (12:30):

While. Yeah.

Samata (12:31):

And so for me, when it comes to fashion, it's a kind of interchanging old and new so that we start to celebrate not just old practices. Like I said, like I'm from a British born Ghanaian, so how my mom used to speak and still speaks about like how they make things, how it school, her entire class did home economics. Like it was a, it was, it was just standard like everyone across genders learnt how to cook so, and do certain things because it was seen as like a skilling for life. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. So because they all learnt home economics, that understanding of how things are made, which is so old, like traditionally it's just so old knowing how to do that was just like standard practice. So there's these old things that were happening. So when I would go to Ghana and we would, you know, go for a wedding or a funeral or whatever it is, you know, we all take our fabric to the same tailor.

Samata (13:20):

We've all got our customized outfits personal to us, you know, but in line with the theme for the wedding funeral or whatever. And so we grew up seeing tailoring, so it was just a thing for us, but now it's considered new. Mm-Hmm <affirmative>. Now the idea that retailers have a space in a retail or a store where you can go and customize something or get it sewn, it's considered new. But if you look at old and you look at images of like even New York or the States, they would have cobbler on the street. They would have tailors and so and so like on nearly every street corner. So I feel like there's different things we can lean on to just detach from this idea of new and lean into just allowing things to have a used cycle, but not letting the word used or old feel like an insult. You know? And I think that's like the basis of the circular economy, for example.

Katelan (14:10):

Budget is a big constraint for a lot of people when they start thinking about sustainable fashion. And I think it's kind of part of this mindset shift because if your clothing budget is like a hundred dollars a month, you can go to Zara or Target and get like four or five things maybe more. But this shift from $5 T-shirts to $50 tshirts is especially hard when everything is so expensive. So I just wondered if you have any thoughts or tips on shifting our mindsets and understanding the process or I don't know, I don't know if that was a process for you or how you've seen other people cope with that?

Samata (14:43):

So prior to kind of even stumbling into sustainable fashion, I literally won a design competition, had to design a dress for the Oscars, that that was how it was. You know, that was the challenge. Designed something, went to la found out that there's a whole sector of the fashion industry that is literally trying to design for people and planet. So if you think about me prior to that, and I'd been like a, a self-taught designer myself. I didn't study it, I just loved customizing things. I have two sisters, so their wardrobes were my wardrobes. And like I would like grab a skirt for my sister, customize it so she wouldn't recognize it. And she'd be like, has anyone seen my denim skirt? And I'm like sitting there chuckling in it, like, ha <laugh>, she'll never know, kind of thing, you know? So my wardrobe prior to knowing what sustainable fashion was, was a mixture of high street, um, fast fashion, my sister's pieces, things that I customized some vintage, like it was a mixture of things you could identify as sustainable now, but I just wasn't using that language.

Samata (15:39):

Yeah. I had a fire and I lost 80% of my thing, so I actually lost everything. Oh my God. Um, all my clothes were damaged from smoke anyway, so I had a reset. So then I had to build a new wardrobe and at the same time as that was happening, I was going on this journey with sustainable fashion. I was like designing this thing for the Oscars and running this campaign. So I started to like be looking at things differently. I still had some pieces that I had prior in my prior life. So the first thing I would say is when we talk about this whole fast fashion high street thing, I get frustrated because I recognize there is a desire for people to access fashion, to access trends, to access through size, through access, through disability. That like a lot of sustainable fashion brands aren't fully catering for anyway, period.

Samata (16:21):

So there's that. So I always have said like, I still have pieces in my wardrobe that I had prior that are from some of these brands, but I have noticed that how things are made and the quality of how things have made has gone down. Mm. So there's one element of yes, you, if you have a desire to purchase trends or be part of trends and you are not seeing that need served by like the brands that identify as sustainable, I can't fault somebody for wanting to participate, not being able to get that and saying, okay, well I'm gonna buy h and m, I'm gonna buy Zara. My questions would be, we need to have conversations with these brands about a how they're making, what they're making, who's making and why it's okay and acceptable for the quality of some of this stuff to be so poor.

Samata (17:03):

Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. Because there should be no justification for saying, oh, well, you know, this costs me X, y, Z so it should fall apart. Like if something costs you $2, $3, $4, $5, I personally can't participate in that. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, because I can't see the story behind which, or the logic behind which in any scenario, someone is not being exploited for me to get a dress that's like embellished, embroidered for like $7. Like someone is suffering in the value cycle because of that. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. So there's like a low that I cannot go. And the people who say like, oh, it's an affordability thing, will buy 50 of those things. So you're kind of spending like $400 and getting like a hall. So you have to have an honest conversation and say like, yeah, okay, there's, there's, it's not an affordability thing because I can spend a portion of what I've just spent on getting 50,000 items for like $2.

Samata (17:51):

I can assign that and buy some better quality items from some more trusted brands and not have so much of a horse. There's like, there's an issue there. But I do wanna recognize that like for the average person going and seeking out a sustainable fashion brand and going and looking for something, and I'm not talking about secondhand vintage or resale platforms. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. Yeah. I just mean on the high street is difficult. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. So I, I try and kind of meet in the middle and say like, if you are going to these specific brands, look in the label, look where it's made, see the transparency on that. It's still your hard earned money that you're saying like, I don't mind if that goes to waste because it was only this amount. So even if you don't care about the value cycle and like potential exploitation and the cycle of how things are made, can we get a bit more of care and like a bit more indignation about it shouldn't be okay for you to sell this.

Samata (18:41):

So I would just say like, it has to be small steps. And my, my wardrobe is like a mixture of black-owned brands, indigenous brands, bit of vintage, bit of secondhand. I still have some of the pieces I had from the high street, but those are pieces I got ages ago that have lasted. I feel like if I tried to get yeah, something similar now it would be cheaper and it wouldn't last as long. And then again, if you're going into those brands, at least go and look for the sustainable category. Like, and sometimes there's some heavy greenwashing in there, you know, but at least if you're going there, try and go for like your natural fibers over your synthetics. Try and go for like your, maybe your recycled alternatives over your virgin. Like try and make small choices incrementally. But I'm not coming from a place of judgment. 'cause I know that we have a lot of work to do as an industry when it comes to providing for everyone.

Katelan (19:31):

Okay. Unless we have some really drastic changes in society, we need close. But there's that stat that we already have six generations of close on the planet. So my tough question is what is the role of sustainable fashion brands in a world that already has enough clothes?

Samata (19:49):

We do already have enough clothes on this planet for the next six generations is the, the figure that's been shared around. And we, we have too many clothes. Yeah. So on one hand we have to lean heavily on the circular economy. Like there is literally no other way. Yes. The circular economy is a concept that isn't just about recirculating clothing through resell and refurbishing and, and repurposing and technical washing and all of the brilliant things it is. But also through the reduction in production. I think a lot of the time when we talk about circular economy, people think about this item going round and round and round. But the, the true like structure of a circular economy, if you look at like the cradle to cradle principles is so much more than that. It's water stewardship, it's renewable energy, it's all of these other things and it's the production of an overproduction.

Samata (20:34):

Yeah. It's literally brand saying we are going to disclose, you know, there's a current campaign I think is the or foundation that speaks volumes. Like we need to know how much is being made by these brands. And we need a commitment to reduce production, I think on the citizen side of things. And I think there has to be an accountability and that's why things like the fashion act, like really like punitive legislative frameworks needs to come into play because it's not enough for us to kind of just applaud effort. There has to be some like legislative framework that it's a current and stick. Like there has to be that. But I think on the flip side of like us as citizens and consumers of clothes, we have to get so creative with how we're using stuff. And I wrote the Sustainable Style Guide for everyone, which is a free resource by the way.

Samata (21:16):

And it's hosted on the Black Pearl website. And in it there's a section about how you can reimagine things and it talks about all the different things that things can become. Like it talks about like fabric becoming patchwork, clip quilts, upcycle tote bags. It talks about scraps of fabric becoming headbands scarves. It talks about making wall art out of things that you love but can't wear anymore. It talks about turning apparel into things like home decor. Like there's so many different sections in it and it breaks down all the different ways that we can make stuff into something else. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. So considering that we have enough clothes for the next six generations, not only do we need to see production going down like a hundred percent, we also need to see us all being more creative about like this stuff that's piling up here. We don't want it ending up washing up on the shores of another country in another space. Yeah. Um, we don't need it back piling in a vintage or secondhand charity shop. 'cause 70% of that is being sent across to different continents, primarily the global south. Anyway, we need to get creative with the stuff that exists and figure out all the different ways where we can engage our global community to become creative again.

Katelan (22:23):

I love that vision. I hope it's, it's sort of this give and take. It's sort of like it's on us to do some stuff to promote these companies doing this, but also to value the, the money that we've parted with and value the, the objects that we've obtained. Yeah,

Samata (22:37):

Exactly. And maybe that's the sweet spot in the balance. We have a role to play as consumers who can be addicted to shopping. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, um, across genders. By the way, <laugh> don't talk enough about men's fashion, but anyway, <laugh>. Um, but yeah, the production side of it. Now let's get into that.

Katelan (22:54):

Okay. So over the past couple years there have been some beloved sustainable fashion brands closed. There was Mara Hoffman, Alana Cone is closing. And I was wondering what do you think has to change either in the economy or how we buy or how we shop in order to make it so that these more sustainable fashion businesses can survive and thrive?

Samata (23:17):

Yeah. Um, and like you, I was, I was really kind of devastated when I I heard about specific brands closing because you know, when people ask you like, oh, who should I be looking for? Yes. Like what should I be buying from? You would give these brands because they have the values, they have the philosophy they're making in a considerate way and they're like the beacons not just for people to talk about them like myself, but also for those brands who are coming up. Yep. You know, they're benchmarking and saying, oh hopefully one day I'll be in that position. But I think it reflects not just like the instability of our industry, it is really unstable right now. Like it's competing with a fast fashion model that's kind of like produced. Some companies are doing like 6,000 styles a day, 52 bucks. Oh my gosh.

Samata (23:58):

Here like, it's like this battle for the citizens' mind, right? Hmm. Um, and then also trying to get people to participate without feeling judged and without feeling like it's a personal critique on their value system if they're not, like there's a lot that sustainable fashion brands have to battle with or come up against. And then on top of that, like I don't necessarily think they always get this, the, um, financial support, structural support. They're like navigating rising and falling costs of inputs and materials. So it's just a whole thing they have to battle against. But what I would say when we look at like what I feel is needed, one is the financial infrastructure and then just like the legislative support, like brands that are trying to produce in a way that's mindful of sustainability from like transparency with like the digital product passport across to like prioritizing sustainable materials.

Samata (24:48):

They should be incentivized, there should be tax cuts, there should be a way that we are develop like developing policy to reward them and make it mm-Hmm. <affirmative> easier for them and recognizing that they have manufacturers that they're also trying to kind of negotiate and do business with. So making it easier for that relationship as well. So it's heartbreaking to me when I see brands that I admire and, and look up to like falling apart. But the reality is that demands on like smaller companies particularly make it nearly impossible for them. And so sometimes they have to sell the company and they're no longer privately held. And sometimes when that happens, there's a, a trade off between the values of the brand and the values of the holding company and that becomes a whole thing as well. Yeah. So there has to be something around capital flow that has to be said so that you know, these brands can retain the values that they still want whilst scaling up.

Katelan (25:41):

Yeah. It's a really tough trade off and hopefully some new brands will emerge and, and will maybe some will reopen. I don't know. I'm very hopeful <laugh> that, that some of them will reopen me too.

Samata (25:52):

And just maybe in a new ecosystem. And the thing I was going to say is maybe just maybe the collaboration we need is the grouping of these smaller players to share resources, to share infrastructure because like a consortium of sustainable brands really working together.

Katelan (26:12):

Yeah. Well thank you so, so much for coming on the show. This has been so insightful. I really appreciate it.

Samata (26:18):

Thank you. Thank you for having me

Katelan (26:27):

With these behemoth fast fashion brands, setting the pace for an entire industry, it's not easy to create a sustainable clothing brand, but they do exist. The commons team has sifted through hundreds of brands sustainability reports to separate the greenwashing companies from the ones that are really walking the walk. We rate brands on a scale of one to five from harmful to best. Our carbon strategy manager, Sophie Janaskie, has been leading this research. So I called her up to find out what you can look for when you're trying to find out if a clothing brand is sustainable. Hey Sophie.

Sophie (27:05):

Hey.

Katelan (27:06):

So you and your team have been researching and rating dozens of clothing and fashion brands for a few months now. When you were looking at all these brand sustainability information and reports, what kind of stuff are you looking at?

Sophie (27:20):

Yeah, so when we look at these brands websites and reports, we're looking for information on a lot of different things. So primarily their materials, how they're promoting slow consumption as well as their just overall accountability.

Katelan (27:34):

I feel like we should maybe start with accountability.

Sophie (27:38):

Yeah. It's a really great place to start because our rating is only as good as the sustainability information that a brand makes available to us.

Katelan (27:46):

That makes sense. So if you have to really dig and dig for sustainability information or it's just not there, that is not a good sign.

Sophie (27:53):

Exactly. If a brand is marketing themselves as sustainable, it's our opinion that it's really important that they have the data and the reporting to back up those claims. Especially larger brands which have some of the biggest impact and have, in our opinion, the most expansive responsibility to be accountable for their energy use, their resource use, the waste that they're creating, the conditions of the people making their products and all of the other kind of metrics that we're looking at.

Katelan (28:25):

Are smaller brands held to the same standard as larger brands?

Sophie (28:29):

That's a really great question. So smaller brands tend to have fewer resources than larger brands, um, which can realistically make it harder for them to have the same level of robust reporting. And also to some extent, smaller brands can be viewed as inherently more sustainable because their operations on the whole are less polluting. So there are um, a couple of different considerations that we take into account when we're looking at company size and what their level of of reporting should be.

Katelan (28:59):

It seems like in this accountability section where you're kind of like determining how good a company's information is, this might be the place where you'd encounter the most greenwashing. I was wondering if there are any red flags that you look for when you're grading a brand's accountability?

Sophie (29:13):

I think a good example of of one type of red flag is looking for completeness of information shared. Okay. So for example, if you're looking at whether a brand is reporting on emissions reduction targets, there's a big difference between a brand who has a target set to cut emissions by 50% from a 2019 baseline by 2050 versus another brand who has a vague commitment to just reduce their overall emissions. Right?

Katelan (29:43):

That's

Sophie (29:43):

Very different levels of granularity and specificity. When you're looking at that type of information, you're really looking for completeness and the full context being presented. And then I think a second piece would be checking in on progress. Hmm. So to continue the example of emissions reductions targets a brand might have targets to decrease emissions, you know, on a, a timeline compared to a baseline, all of those great things. But it might be the case that over the past few years they've actually increased their emissions. And so we wanna also be mindful not only are they setting robust targets, but how are they actually progressing against those targets.

Katelan (30:22):

Labor is also accounted for in this accountability section, right?

Sophie (30:27):

Yeah. As part of a brand's accountability, we also consider how transparent brands are about the factories that uses. So looking are they, you know, reporting the names and locations, are they tracing their supply chain? We are also looking for supplier codes of conduct and what's contained within them as well as their policies on, on audits.

Katelan (30:48):

Okay, cool. So we've got our accountability section, we've got our base level. So now diving into the materials section, this seems like the place where we're really gonna dig into emissions.

Sophie (30:59):

That's exactly right. So in the fashion industry, over 70% of greenhouse gas emissions actually come from upstream activities. Think things like raw material productions like growing cotton or preparation, processing, actual production. So think like sewing and the actual construction of garments. All of that fits under our materials section.

Katelan (31:23):

How do you go about determining how sustainable these upstream activities really are?

Sophie (31:28):

Yeah, so the first thing we look at is the raw materials that brands are using to make their clothes or shoes.

Katelan (31:36):

I'm assuming that eco-friendly materials would be ones that are not made from plastic.

Sophie (31:41):

Not quite. It's a little bit more complicated than that, so, okay. Some examples of sustainable fibers could include organic cotton or recycled materials, whether that's recycled cotton or even sometimes recycled synthetics. Okay. Um, examples of unsustainable fibers include conventional cotton, um, and then virgin nylon or polyester visco rayon, those types of materials.

Katelan (32:05):

What makes those, you know, conventional cotton rayon, visco, what makes those less sustainable?

Sophie (32:11):

Yeah, so it's definitely a spectrum. Taking cotton as an example, organic cotton can be one of the most sustainable fibers that you can use. While on the flip side, conventional cotton can actually be one of the worst. It's the same plant, it's the same material just grown differently.

Katelan (32:30):

That's so fascinating. What about synthetic fabrics? Like polyester?

Sophie (32:34):

Yeah, polyester and other synthetics are derived from fossil fuels. So purchasing them, especially when they haven't been recycled from an existing feedstock can help support the fossil fuel industry, which is definitely an an area we're trying to avoid. Right. And then a few other issues with synthetics include when you wash them or you wash clothing that contains synthetics, that actually sheds microplastics, which pollutes our water and can cause you know, a host of environmental issues. They're also pretty energy intensive to make and just less biodegradable.

Katelan (33:11):

Got it. So when we're looking at the sustainability of a material, are you also looking at the emissions factor too?

Sophie (33:18):

So we definitely look through an emissions lens throughout our

Katelan (33:23):

Rubric. Okay.

Sophie (33:24):

But emissions can also be a pretty good indicator of other benefits and impacts around things like soil health, worker health and safety, water quality, um, kinda a host of other metrics. So again, continuing with organic cotton, one of the benefits of organic cotton obviously is that it's lower emissions, but at the same time it, it represents all of these other co-benefits as well. Right.

Katelan (33:49):

And in this section in materials we're also looking at energy use, right?

Sophie (33:53):

Yes. And so, uh, material sourcing is just one piece. We also wanna look at the different production practices and one of those is their energy strategy. Okay. So this includes if a brand is using renewable energy at all, uh, in its operations as well. We're also looking at, uh, energy efficiency measures.

Katelan (34:14):

Um, I have to ask about packaging too.

Sophie (34:16):

Yes. So packaging is super important to shoppers. We look to see what the brand is doing both to minimize its overall packaging and just reduce the amount of material they're using as well as avoid plastics and shift towards more eco-friendly materials.

Katelan (34:32):

Like if you're looking at um, an e-commerce package you receive from a brand, like that packaging piece is not a huge fraction of the emission. So I'm just wondering like why do you think it's so important to us as, as consumers, as shoppers?

Sophie (34:44):

Yeah, that's definitely true. So if you're looking at a product and its associated lifecycle footprint, packaging does make up a relatively small proportion of its overall emissions footprint. But I do think it is still important to shoppers because packaging's just one of the first things that they experience when they're making a purchase. And more eco-friendly folks are definitely going to notice when there's a lot of excess waste, especially if that excess waste is plastic.

Katelan (35:14):

So I want to dive into slow consumption now. When we think about a brand sustainability, thinking about slow consumption may not be the first thing that comes to your mind. Yeah,

Sophie (35:23):

For sure. We thought it was really important to look beyond just a brand's product and supply chain when we're considering the overall sustainability of a brand. We also wanna be looking at how they're curbing over consumption culture and also taking responsibility for their product in its full life cycle.

Katelan (35:45):

I love that because a lot of brands, especially fast fashion brands, are doing whatever they can to get us to just buy new things like every week basically.

Sophie (35:54):

Yeah. And so when we're grading, uh, a brand slow consumption practice, we're looking at, you know, their marketing to see if they're encouraging over consumption or if they're explicitly encouraging mindful consumption. So we're looking at their email practices, we're looking at the way that they're talking about their positioning and their ethos on their brand pages. We're looking to see how frequently they're releasing new items. Um, there's a lot of pieces that kind of go into the consideration of, of that section.

Katelan (36:23):

I think we've all been there before where you maybe sign up for like a discount code or something and then all of a sudden you're getting like three emails every day to get you to buy stuff. It's so annoying.

Sophie (36:32):

Yes, definitely. And it, it really starts to influence your behavior too. If you're like every time you open your inbox, you've got a new discount code, it can be kind of challenging to fight that impulse. Another part of the slow consumption criteria is looking to see if brands are practicing slow fashion.

Katelan (36:50):

So slow fashion would be making new styles less often, like a smaller collection.

Sophie (36:57):

Yes. And this goes a long way to slow the trend cycle. And so trends are often what make us feel like we're constantly needing to buy new stuff. We're also looking to see what brands are doing to keep their clothing out of landfills.

Katelan (37:11):

I have noticed that many more brands are offering buyback programs where they buy back and then resell secondhand items from their customers, which is really cool.

Sophie (37:21):

Yeah, takeback programs are really great. Some brands also go the extra mile and are also offering repair services or even lifetime warranties on their products. And these kinds of longevity investments mean that it's in a brand's best interests to make something that lasts, but when or if it does break, they're gonna be there to help um, get it back into working order.

Katelan (37:44):

So I have to ask, you know, there are these really big fast fashion brands that we know are bad. Like you know, your sheen, your czar, your h and m, but I was surprised to see like really nice brands or more nice brands like Uniqlo and free people get our lowest rating

Sophie (38:00):

In my opinion. There's room for differentiation here as well. So h and m is pretty objectively doing better in terms of its sustainability initiatives than say some of the ultra fast fashion brands like Xian. But h and m is still pumping out a lot of clothing, which there's sort of no way to get around it. It's fueling over consumption. And so there's a bit of a cap on how sustainable a fast fashion brand can be if their business model is relying on this over consumption. And so some brands can also do a really great job of seeming to be sustainable. So a brand's elevated aesthetic or higher quality items can totally make you think, hey, this can't be as bad as other fast fashion brands. Right? So when something is really inexpensive, I think that should also throw off some alarm bells and that might be, you know, where these materials being sourced from.

Sophie (38:59):

What does the compensation of workers in the supply chain look like? I think these are some really real questions that come up when you have really inexpensive items. And on the flip side, if something is more expensive, does that make it inherently better? I've seen this come up a lot where it seems like the quality of things is seeming to go down despite them costing a pretty penny. And this is really important to to slow consumption because the longer something lasts and the more high quality it is, the less often you have to buy it. So ideally, if you are making that investment in a more expensive piece, you wanna make sure that it's something that is quality, that it's gonna last. And it's challenging because it, a higher price tag doesn't necessarily indicate higher quality.

Katelan (39:46):

Totally. I think a great way to get low cost that are more sustainable and maybe higher quality is to choose secondhand. I love shopping at a thrift store.

Sophie (39:56):

Absolutely. I think that's a really great option. Every secondhand store and thrift store gets two thumbs up from us. And another important way to save money on clothes and over consumption is to just buy fewer clothes. <laugh>,

Katelan (40:10):

I have one more question. With all the brands that you've looked at, has it changed how you personally think about shopping for clothes?

Sophie (40:19):

That's such a good question. I think the first thing that comes to mind is that now more than I ever have done in the past, one of the first things I do when I'm looking at honestly a new or used item is I read the materials tag. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. And part of that is just having more context on the impact of those materials. But I've also just personally noticed that clothes made of synthetics for me just don't seem to last as long and they just don't really look the way that I want them to look. Yeah. Oftentimes I honestly just think that more sustainable materials look nicer. <laugh>.

Katelan (40:55):

I totally agree with you. I think once you start making that switch in your mind as to like, I'm gonna start buying more sustainable fabrics, it is really hard to go back. It's hard to put something on you that's like all a hundred percent polyester. You can really feel the difference. Yeah,

Sophie (41:08):

I totally agree.

Katelan (41:09):

Well, thank you so much for all the work that you've done to rate all these brands and for coming to talk to us today.

Sophie (41:14):

Of course. Thanks Katelan.

Speaker 15 (41:21):

So

Katelan (41:22):

How are you inspired to make your wardrobe more sustainable? Maybe you can repair or tailor clothes that you haven't gotten a lot of wear out of or post a clothing swap for a reciprocal closet upgrade. You could choose secondhand first before buying new clothes. And when you need to buy new, you can search out brands that are using more climate friendly practices and materials commons is here. To help with that, just go to brands dot the commons.earth. This is our season finale of our second season of Second Nature. I can't believe we only just started this show in April. Woo. Thank you so much for listening. If you're new to the show and you liked this episode, there are 17 more where that came from. We've done an episode on fast fashion, sustainable gifting over consumption. There are so many goodies, so give them a listen.

Katelan (42:15):

And if you've been with us for a while, thanks for coming back and for making this show part of how you care for the climate. If you're digging the show and you want us to keep it going, there are a couple things you can do to help our small team out. Number one, review and rate the show. This helps so much because we wanna know what you think. Your feedback is super valuable and it also helps to get more ears on the show. Number two, follow us on Instagram at Second Nature Earth. Common Social Media manager, Amaya Wadsworth, is always sharing memorable, practical tips about all the topics we talk about on the show. So if you like Second Nature the podcast, you're gonna love our Instagram. We're not accepting submissions for season three quite yet, but we will be very soon. If you haven't subscribed to the show yet, make sure you do that so you don't miss our call for submissions. Of course, I have to thank the listeners from today's episode who shared how they practice sustainable fashion in their own lives today. You heard from this episode and every episode this season was edited and engineered by the incomparable, the fantastic Mr. Evan Goodchild. It was written and produced by me, Kaitlyn Cunningham.

Katelan (43:33):

I hope you're able to take some time to recoup and hibernate and recharge this winter. We certainly will be and we will see you next season. Bye.

.avif)